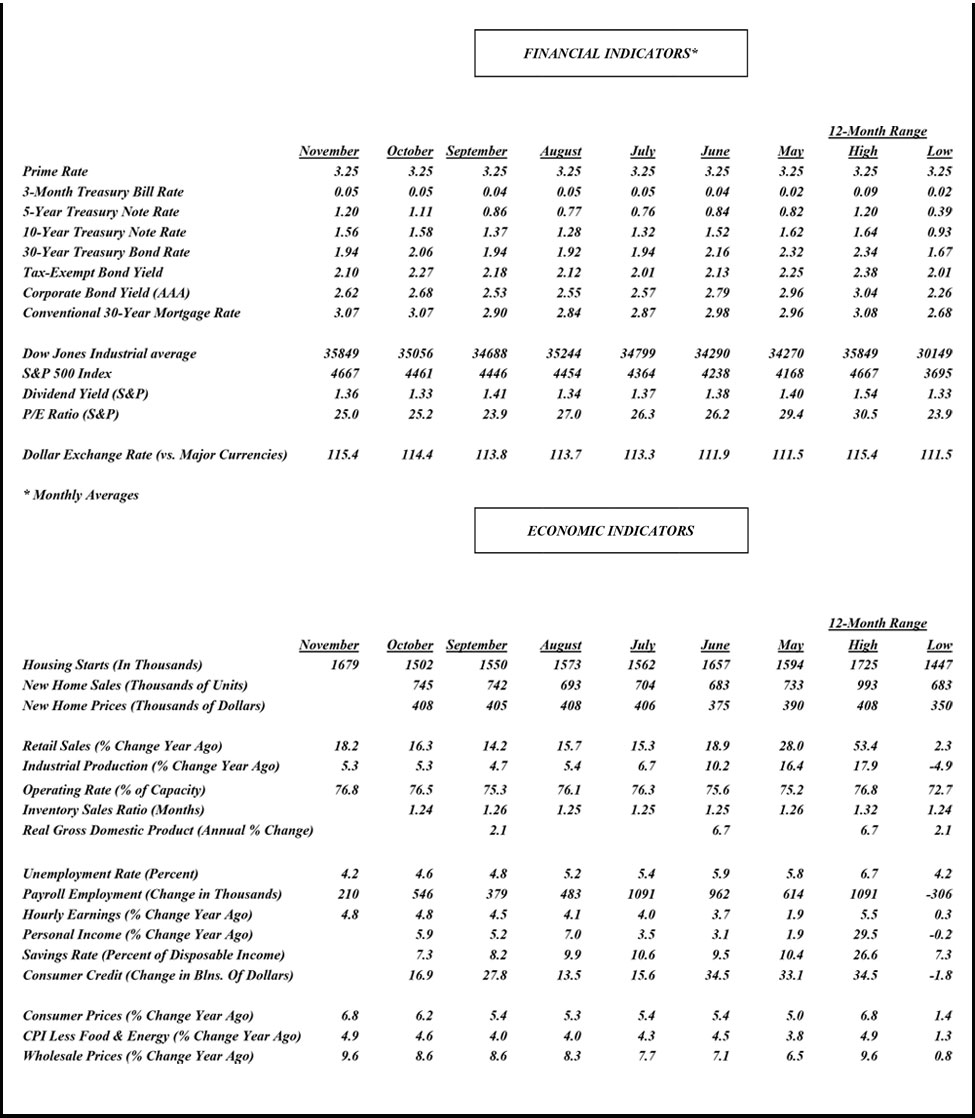

Fear & Inflation Cast a Shadow Over 2022

It may not feel like it given the resurgence in Covid health concerns, elevated inflation, and heightened financial market volatility, but the U.S. economy is doing quite well heading into the new year. Unemployment is falling rapidly, people are shopping freely, household balance sheets are solid, and businesses are enjoying record profits. The recovery from the 2020 pandemic recession, the deepest – although shortest – since the Great Depression, has been swifter and stronger than any of the previous postwar upturns.

But while there is plenty to celebrate about the recovery, the economy has not fully healed and risks to the outlook loom large. The level of output is still 2.5 percent below the pre-pandemic trend, nearly 4 million of the 22.3 million workers that lost jobs in early 2020 are still missing, and wages, after adjusted for inflation, remain below where they were in March 2020.

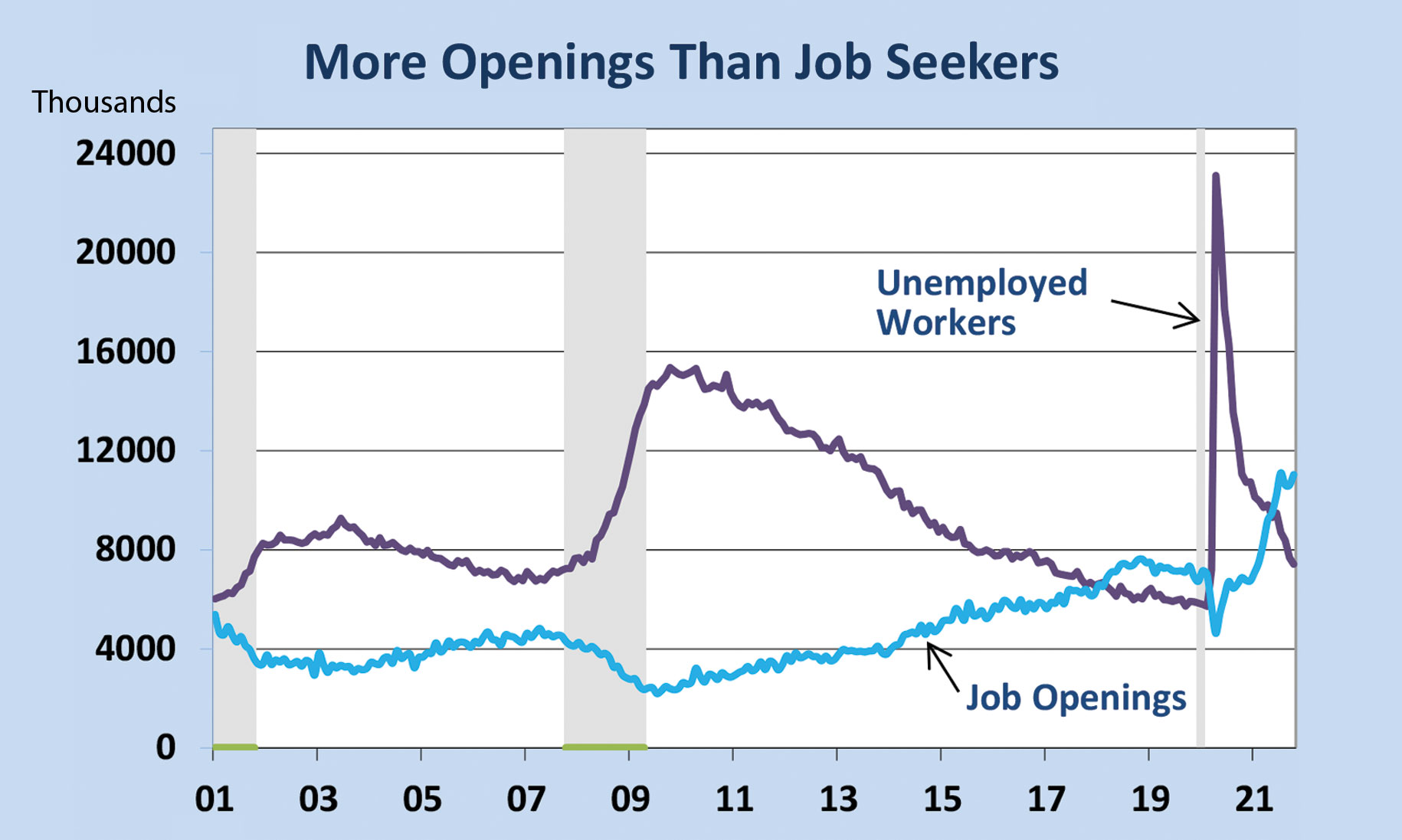

While job growth has been strong, businesses are desperately struggling to fill open positions, as the share of population in the labor force remains well below its pre-pandemic level. Health concerns, childcare responsibilities, and a wave of early resignations are holding back the supply of labor.

While job growth has been strong, businesses are desperately struggling to fill open positions, as the share of population in the labor force remains well below its pre-pandemic level. Health concerns, childcare responsibilities, and a wave of early resignations are holding back the supply of labor.

Despite these headwinds, the economy is winding up a year of solid growth, with GDP on track to advance by around 5.5 percent. What’s more, it is heading into 2022 with solid momentum, as the fourth quarter is expected to grow by an eye-opening annual rate of more than 7 percent. Yet as we noted at the outset, not everyone is feeling the joy; household sentiment has been sinking dramatically in recent months, with some surveys reporting a downbeat mindset comparable to recessions. One reason, of course, is the resurgence of Covid, driven by the new Omicron variant..

Another is the astonishing revival of inflation, which is running at the strongest pace in 40 years and is prodding the Federal Reserve to take corrective action sooner than it had planned just a month ago. Both the intractable health crisis and the hawkish pivot of the central bank cast a dark shadow over the outlook. No one knows how severe the latest Covid wave will be, and many fear that a policy mistake could choke off the expansion. The coming year still looks promising, but the downside risks are rising.

Passing the Baton

As the curtain falls on 2021, the new year offers many promises but is fraught with uncertainty. On the positive side, the fundamentals are solid. Unspent funds that couldn’t find outlets due to pandemic restrictions, means consumers are in a good position to sustain spending at a healthy pace. Final figures are not yet in, but holiday sales were strong, limited primarily by a shortage of goods that supply bottlenecks prevented from reaching stores in time for the season.

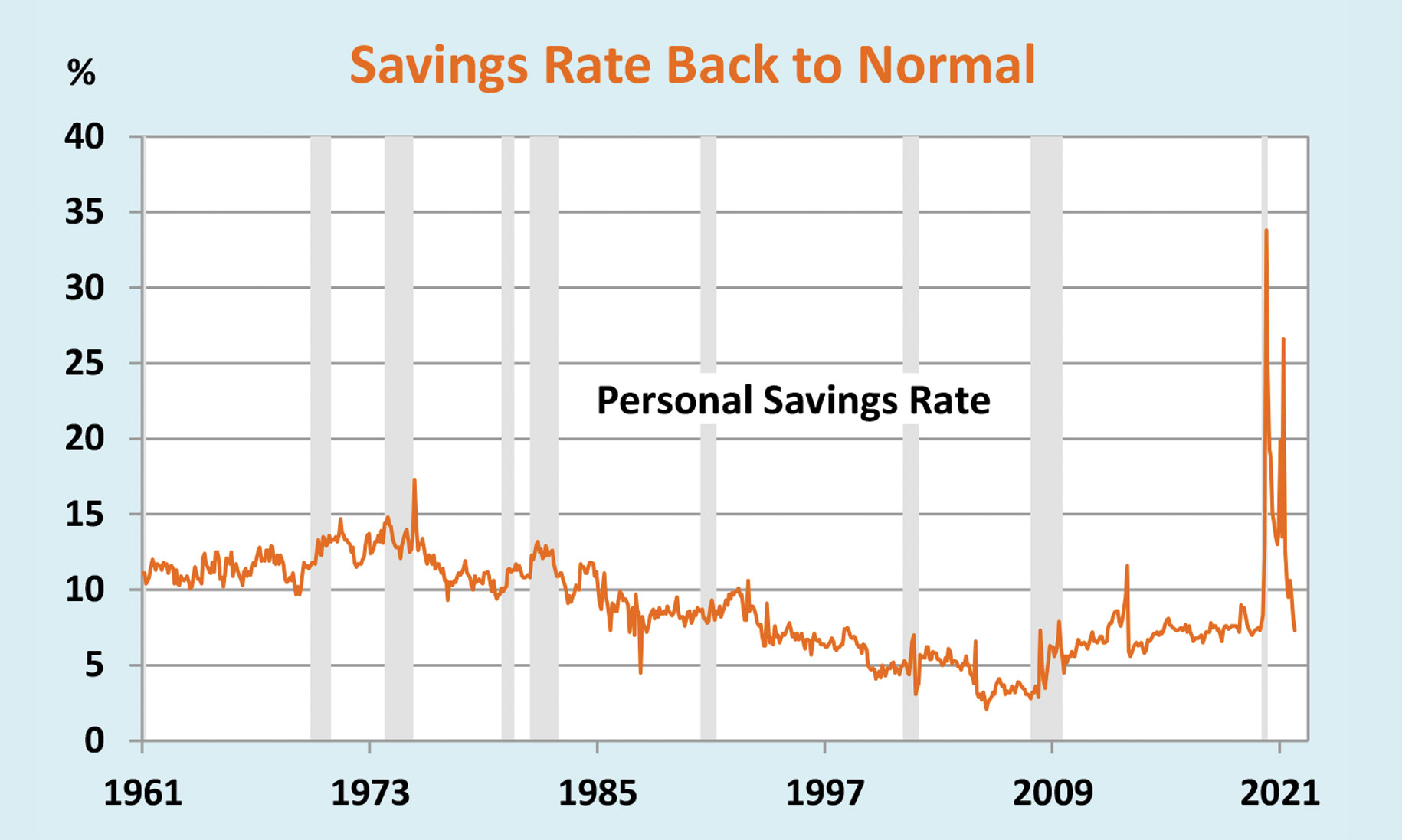

True, the stimulus-fueled underpinnings that propelled the strongest consumer spending increase in 2021 since World War II is not sustainable. For one, most of the stimulus checks have already been spent, particularly among lower-income households. For another, pandemic emergency unemployment programs have ended and, unless Congress extends it, so too has the expanded child- care tax credit that gave families $300 a month for each child. The last check went out in December. The personal savings rate, which shot up as high as 33 percent last April, is now down to just over 7 percent, in line with pre-Covid levels. There is still more than $2 trillion in excess savings from unspent funds sitting in bank accounts, but most of it is held by wealthier households who tend to retain high savings balances.

care tax credit that gave families $300 a month for each child. The last check went out in December. The personal savings rate, which shot up as high as 33 percent last April, is now down to just over 7 percent, in line with pre-Covid levels. There is still more than $2 trillion in excess savings from unspent funds sitting in bank accounts, but most of it is held by wealthier households who tend to retain high savings balances.

But the purpose of the massive fiscal aid disbursed over the past year was to tide people over until the private sector could retake the mantle of growth. That handover is well underway, thanks to a robust job market that is fattening paychecks of existing workers and restoring most of the ones that were lost during the pandemic. While government transfer payments are rapidly diminishing, labor compensation is making up the difference. Since March, wages and salaries have increased by a monthly average of 12 percent from year-earlier levels, while government transfer payments have been cut in half, from $8.1 trillion in March to under $4 trillion in October.

Renewed Health Fears

When the Delta wave of the virus, which caused activity to stall over the summer, peaked and then faded rapidly in September and October, hopes were high that consumer and business behavior would return to normal. Workers would return to offices, boosting the fortunes of small businesses in surrounding neighborhoods, consumers would reengage in social activities, including dining out, going to concerts and sporting events, satisfy postponed travel and hotel plans, all of which would jump-start the service sector, which is the largest part of the economy.

For a while, that dynamic played out. But in November the Omicron variant emerged and its rapid spread is starting to curtail the economy’s momentum. Vaccine and mask mandates are being reinstated in many states, schools are partially closing again, theaters are canceling shows and, most important, consumers are starting to behave more cautiously. Bookings at restaurants and bars slipped markedly in December, according to data provided by the reservation site, Open Table. The health implications of the Omicron variant are still highly uncertain. But given the variant’s apparent greater ability to overcome vaccines and re-infect those that have previously caught Covid, it seems that the peak of the current Covid wave could well surpass the last peak in August.

Still, it is too early to determine if the economic impact from this variant will be as disruptive as previous ones. Early health data suggest that Omicron produces less severe symptoms than earlier variants. The government is unlikely to impose lock-down restrictions given the political backlash that could ensue and the public appears to have developed a case of pandemic fatigue, reluctant to make as many sacrifices as the past two years. With vaccination rates higher and more tools to combat the virus available, including the promising development of a Covid pill that could swiftly become broadly distributed, there is every reason to hope the damage to the economy could be contained.

Stubborn Inflation

That said, Omicron is not the only influence dragging down consumer sentiment. According to just about every survey, inflation is the number one worry among households. Prices of most everything from food to gasoline to rents are driving the fastest increase in the consumer price index in almost 40 years. The upsurge has been particularly jolting for consumers who have become accustomed to stable prices over the past two decades, averaging under 2 percent a year. In November, the CPI shot up to 6.8 percent from a year ago following a steady acceleration since piercing 2 percent in March.

For most of the period, policymakers showed little concern. Over the first few months during the spring, the general view was that the elevated inflation data was more statistical noise than anything else, since prices were being compared to the depressed levels of early 2020 when the pandemic shut down the economy, prompting sharp price cuts. As inflation accelerated over the summer, the Fed continued to believe that upward pressure was coming from “transitory” forces related to the reopening of the economy that were poised to subside as economic conditions normalized.

But the return to normalcy has yet to occur, and the inflation upsurge has been stronger and more persistent than anyone envisioned, including the Federal Reserve. The supply chain disruptions preventing goods from reaching stores and hobbling the delivery of parts to manufacturers are still front and center. The labor shortage that is plaguing a wide swath of businesses still hasn’t eased despite the termination of enhanced unemployment benefits. With demand still robust amid these supply restraints, the time-honored recipe for ever-escalating price increases is firmly in place.

The Fed Pivots

At its mid-December policy meeting, the Fed finally retired the term transitory to describe inflation and decided that bringing it under control was more important than stimulating the economy to promote more employment. Hence, the pandemic-inspired emergency bond-buying program, aimed at providing liquidity and keeping interest rates low, is being withdrawn at a swifter pace than planned just a month earlier. If the withdrawal of support proceeds at the new pace the program should end by March, after which the Fed is expected to start raising interest rates.

While the Fed is clearly unnerved by the severity of the inflation upsurge, it is even more concerned that households and businesses will expect higher inflation to persist. That, in turn, would alter purchasing and wage-setting behavior, entrenching inflation more firmly in the economic fabric and requiring harsher corrective measures to control it, bringing on a recession. So far, however, inflation expectations have not become unmoored. Households do expect inflation to accelerate over the near term – the next year or so – but recede back close to pre-pandemic levels over the longer-term, so their purchasing habits are not likely to change. The financial markets are also pricing in tame inflation over the longer term. Indeed, long-term interest rates have hardly budged since the Fed’s last policy meeting.

The Fed’s decision to withdraw monetary support at a faster pace has been favorably received by investors and among most economists, whose main fear until recently was that policy was falling behind the inflation curve. However, with the onset of Omicron and the lack of fiscal support next year, there is the growing risk that the tighter monetary policy envisioned by the Fed might be too much for the economy to bear. The central bank does not have a very good record of bringing about a soft landing for the economy, and, the challenges next year will be even more difficult to navigate.

Perhaps the most important message from the Fed’s swifter removal of emergency support is that it gives it more flexibility in deciding when and at what pace to change interest rates in 2022. That flexibility works both ways – faster or slower, and lessens the risk that a policy mistake would either choke off the expansion or inflame inflation.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |