Fading But Still Sturdy Profits Should Sustain Growth

Although the coronavirus recession ended two years ago and the U.S. economy embarked on a remarkably strong recovery, many commentators are sounding alarms that a recession is just around the corner. While we are not in that camp – yet – it would be foolhardy to dismiss those claims are out of hand. Indeed, there are more than enough triggers to at least acknowledge the rising risk of a downturn. These include surging inflation, robbing workers and households of purchasing power, an aggressive rate-hiking campaign by the Federal Reserve to curb the inflation outbreak, the confidence-shattering war in Ukraine, as well as Covid-related lockdowns in China that are exacerbating supply-chain shocks and amplifying inflationary pressures.

These triggers have already roiled the financial markets. Through late-May, the stock market had its worst start to a year since 1970, with the S&P 500 down 18 percent. Bond yields have risen substantially, driving up borrowing costs for the Treasury, corporations, and households, particularly for home buyers who have seen the cost of carrying a mortgage increase by 30 percent since the start of the year. A key recession signal flashed recently when short-term rates rose above long-term yields, resulting in a yield-curve inversion that has historically foreshadowed downturns.

These are worrisome events that decision makers ignore at their peril. That said, there are few signs of anyone burying their head in the sand. The Federal Reserve may have waited too long to abandon its turbo-charged easy policy but it is now on the proper path to rein in inflation. Even so, it is far less confident of bringing about a soft landing – reducing inflation without choking off the recovery – than it was earlier in the year. Fed Chair Powell recently admitted that recession risks have risen and a soft landing will take a lot of luck as well as skilled policy management. Likewise, investors are hardly looking at the future through rose-colored glasses, as evidenced by their dumping of risky assets and sizable declines in stock prices. Being prepared for a recession does not, of course, prevent one from occurring. But neither does it mean that one is inevitable. While the risks have risen, there are compelling reasons to believe the economy will continue to grow, at least over the foreseeable future.

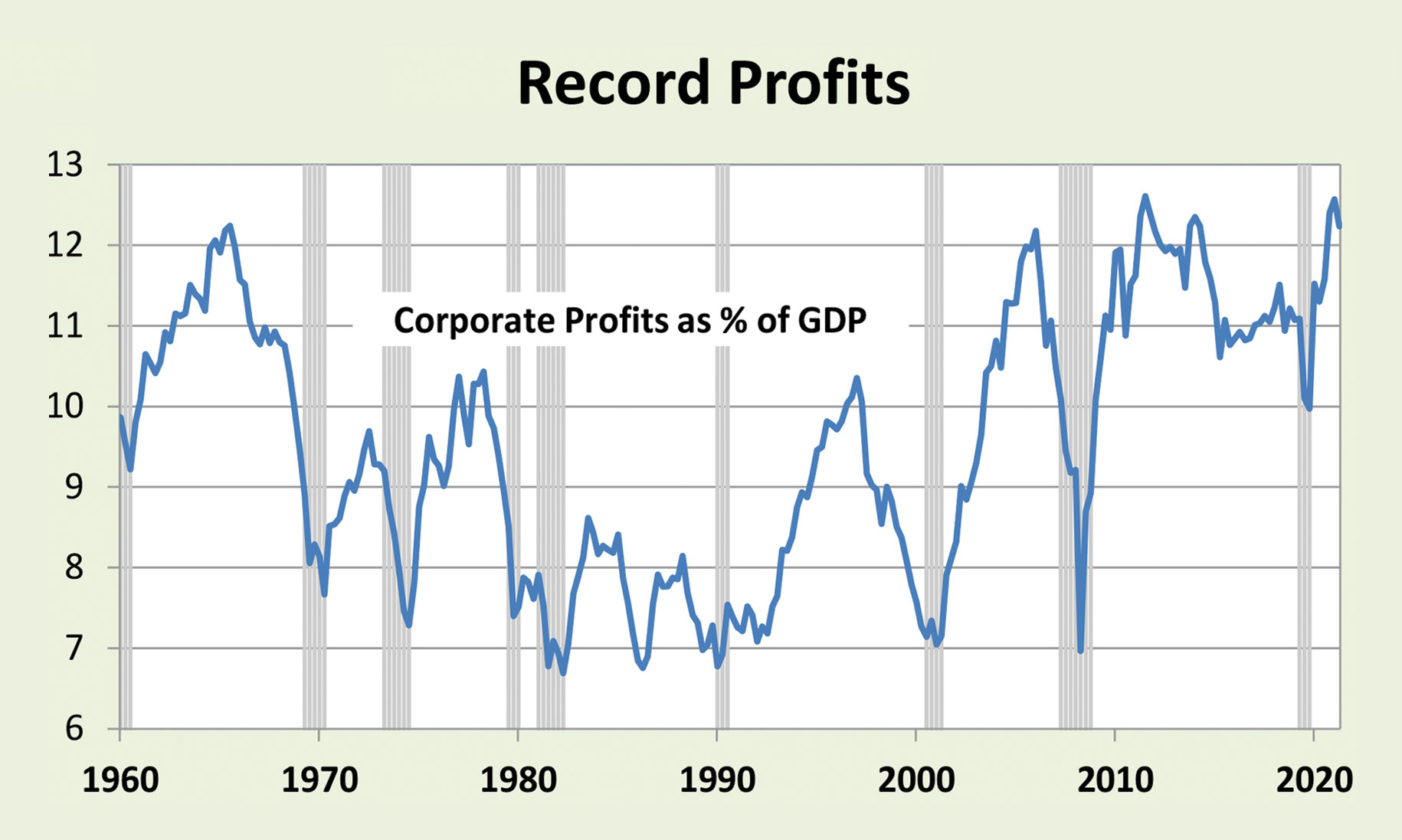

Buoyant Profits

Although the swirl of events has cast a shadow over the economic landscape, businesses continue to enjoy buoyant profits. Since profits are a key driver of hiring and business spending, the longer they remain elevated, the better the odds that the economy will stay afloat. Since the end of the recession, economy-wide profit margins – defined as before-tax profits as a share of GDP – have increased from 10 percent to an all-time high of 12.6 percent in the third quarter of 2021 before slipping to 12.2 percent in the fourth quarter.

Clearly, the bottom line of corporate balance sheets has benefited from top-line growth in revenues. Fueled by a vibrant consumer base armed with more than $5 trillion in pandemic stimulus checks and tax breaks, businesses enjoyed an astonishing increase in demand over the past two years. Even with lockdown restrictions and health fears that discouraged spending on in-person services, the entire drop in consumption during the recession was recovered within a year. Since then, households have continued to spend at a break-neck pace, driving consumption above where it would have been had the recession never occurred, based on the trend in effect prior to the pandemic.

Clearly, the bottom line of corporate balance sheets has benefited from top-line growth in revenues. Fueled by a vibrant consumer base armed with more than $5 trillion in pandemic stimulus checks and tax breaks, businesses enjoyed an astonishing increase in demand over the past two years. Even with lockdown restrictions and health fears that discouraged spending on in-person services, the entire drop in consumption during the recession was recovered within a year. Since then, households have continued to spend at a break-neck pace, driving consumption above where it would have been had the recession never occurred, based on the trend in effect prior to the pandemic.

But robust demand is only one influence driving profits. The other, just as important, is pricing power. Simply put, corporations were able to pass on rising labor and material costs to their customers, and then some. The unusually high degree of pricing power has been a key feature of this cycle’s margin expansion. It also, together with the strengthened bargaining power of labor, underpins the rampant inflation that has become the main economic scourge in the nation. How long companies can embellish their bottom lines depends on how long they can continue to cover rising labor and other costs with price increases.

Labor Costs To Stay Elevated

Compensation costs – by far the largest share of corporate expenses and a crucial determinant of profitability – has accelerated in recent quarters. That’s not surprising since competition for workers is fierce, with 1.9 job openings for every unemployed worker. In the first quarter, the employment cost index – the government’s comprehensive measure of labor costs that includes both wages and benefits – staged its biggest quarterly jump since 1990, climbing 4.5 percent from a year ago from 3.9 percent the previous quarter.

Not only has the rate of increase accelerated, so too has the share of employees receiving bigger paychecks, with 80 percent of industries reporting faster compensation costs in the first quarter. Leading indicators suggest that wage pressures will not ease anytime soon. Amid a very competitive job market, workers are quitting at a record pace, either lured by higher paying opportunities elsewhere or confident that one can be found quickly. This is a time-honored sign workers still have the upper hand in the labor market. Another indication of worker bargaining power can be found among small businesses, which employ most workers. According to the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), the share of small firms that plan to raise worker compensation over the next three months is the second highest on record.

Not only has the rate of increase accelerated, so too has the share of employees receiving bigger paychecks, with 80 percent of industries reporting faster compensation costs in the first quarter. Leading indicators suggest that wage pressures will not ease anytime soon. Amid a very competitive job market, workers are quitting at a record pace, either lured by higher paying opportunities elsewhere or confident that one can be found quickly. This is a time-honored sign workers still have the upper hand in the labor market. Another indication of worker bargaining power can be found among small businesses, which employ most workers. According to the National Federation of Independent Businesses (NFIB), the share of small firms that plan to raise worker compensation over the next three months is the second highest on record.

With the job market still robust, any easing of wage pressures is not imminent. The only way companies can mitigate the stress of rising labor costs – besides raising prices – is through productivity gains. If workers generate more output per hour, the additional revenues can be used to pay higher wages and unit costs would not increase. But strengthened productivity has not been a friend to businesses this year. In the first quarter, total output (GDP) contracted even as worker hours increased, resulting in a 7.5 percent plunge in productivity and a corresponding spike in unit labor costs. Hence, businesses were forced to raise prices aggressively to protect the bottom line.

Challenging Outlook For Profits

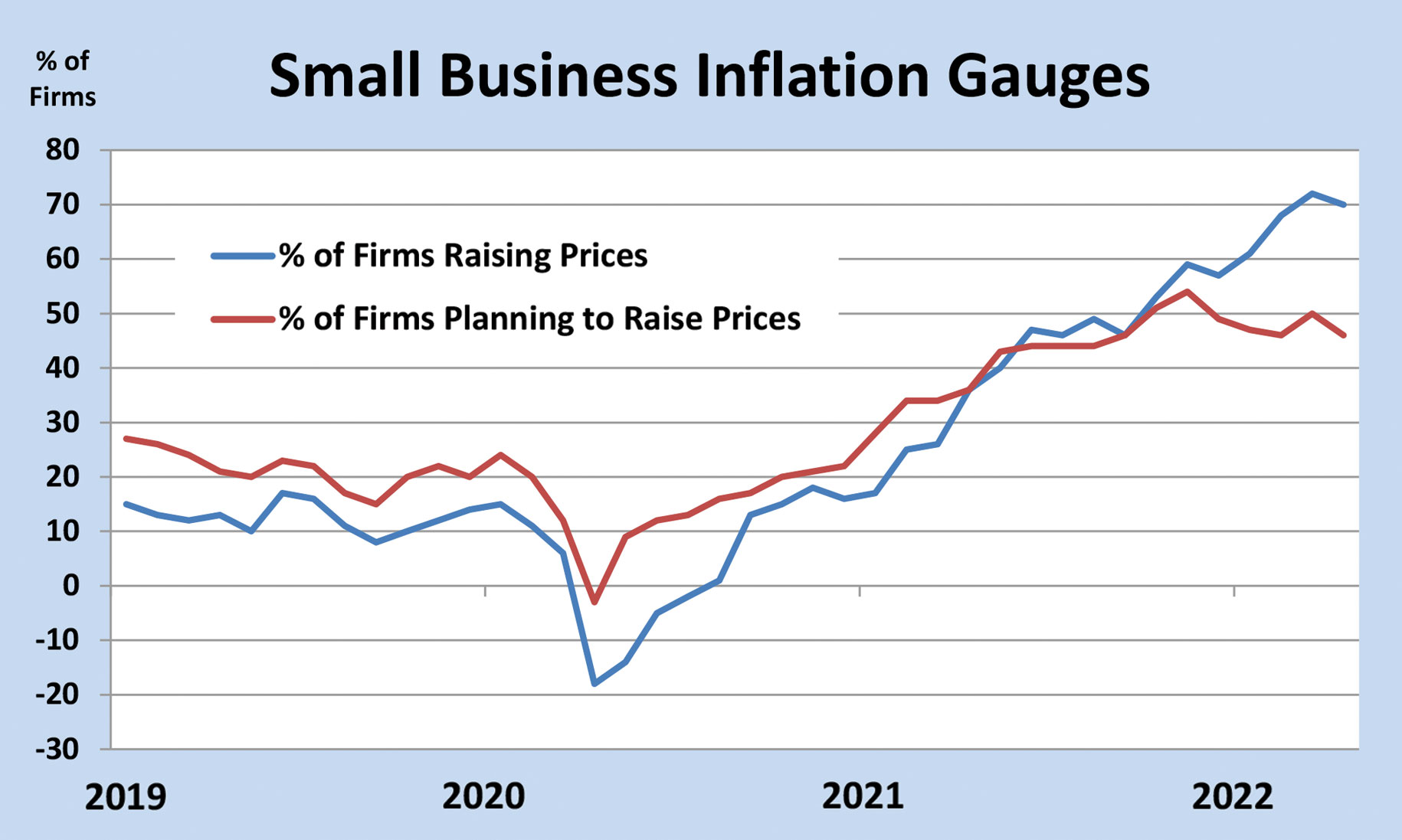

Needless to say, when companies can raise prices faster than unit labor costs increase, inflation accelerates. This is precisely what has been happening, stoking the steepest inflation rate seen in nearly 40 years and sustaining the historically high level of profit margins. According to the aforementioned NFIB survey, a staggering 70 percent of small business owners raised their prices in April. Importantly, the sturdy increase in retail sales that month indicates that consumer were willing to accept those price increases.

However, this is not a sustainable trend, and signs of consumer resistance are already emerging. Some major consumer-oriented companies reported disappointing earnings results in May, including Walmart and Target, largely because customers shunned higher-priced big-ticket items, and sales revenues failed to keep pace with rising labor and other costs. This is not surprising, as household surveys reveal that inflation is eating into budgets and eroding confidence. Along with the plunge in consumer confidence in recent months to the lowest point in more than a decade, households are also scaling back their buying plans.

However, this is not a sustainable trend, and signs of consumer resistance are already emerging. Some major consumer-oriented companies reported disappointing earnings results in May, including Walmart and Target, largely because customers shunned higher-priced big-ticket items, and sales revenues failed to keep pace with rising labor and other costs. This is not surprising, as household surveys reveal that inflation is eating into budgets and eroding confidence. Along with the plunge in consumer confidence in recent months to the lowest point in more than a decade, households are also scaling back their buying plans.

Hence, companies are faced with the difficult choice of restraining price increases or risk losing sales. Early signs are that they are choosing the former. Again, looking at the NFIB, the share of small businesses planning to raise prices over the next three months slipped to 46 percent in April from a record 54 percent last November. That’s still a high share historically, but it indicates that business pricing power is losing some strength.

Implications For The Economy

This would be good news for the Fed, as it suggests that interest rates do not have to increase as steeply to curb inflation than otherwise, reducing the risk of a recession. But it is bad news for profits because costs are continuing to increase. Prices of commodities used for production remain under pressure due to the war in Ukraine and China’s Covid lockdowns. Meanwhile, labor shortages will continue to lift wages as long as the demand for workers stays strong.

However, if price increases start to slow, so too would inflation expectations, which would have a positive feed-back on labor negotiations. Workers would feel less urgency to demand ever-escalating wage increases to compensate for eroding purchasing power. But in today’s very tight job market, workers are still in a strong bargaining position, so labor costs are likely to recede more slowly than prices, putting more of a squeeze on profits. Odds are, the peak in profit margins is behind us.

Importantly, shrinking profit margins is a time-honored trend during the late stage of a business cycle. It does not mean that a recession is just around the corner. Every recession since 1960 was preceded by pronounced margin contractions, but the lag time has varied widely – from 12 months to more than five years. A lot depends on the speed of margin erosion and how aggressively employers respond by laying off workers, driving up unemployment.

Going into this year, companies had a record cushion of profits to work with, which should buy them time to get costs under control before taking drastic recession-inducing measures. Historically, employers hold on to their workers during the late stage of an expansion even when demand starts to weaken. One reason is that they need time to assess if the weakness is temporary or the start of a permanent pullback in sales. Hiccups occur during expansions and it is difficult to modify the size of a workforce to align with temporary shifts in sales. Ultimately, the fate of business profits will depend on revenue growth. If the Federal Reserve can skillfully manage its anti-inflation policy without choking off demand — accomplishing a soft landing — it would silence the recession alarms now ringing in the financial markets.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |