From One Challenge to Another

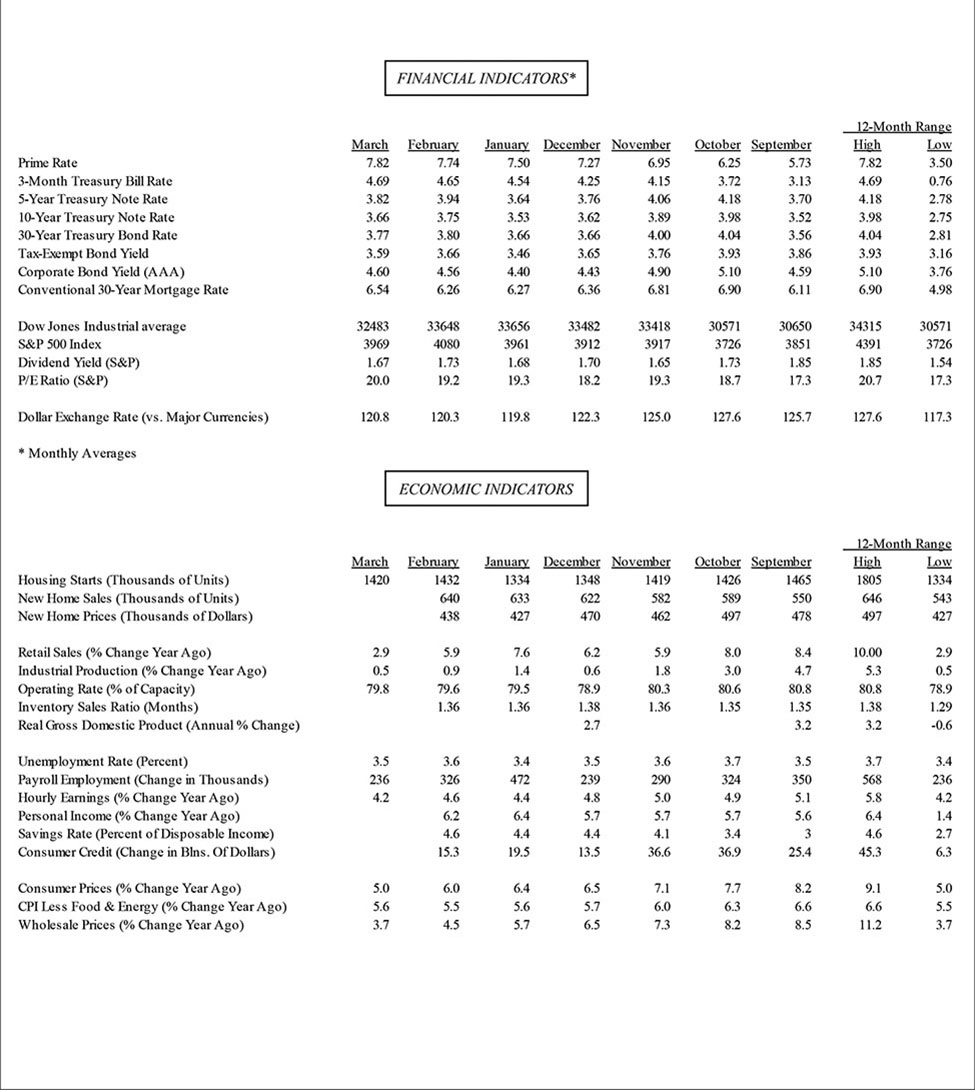

While the challenges that rocked the financial markets in March have been defused, their aftereffects are rippling through the economy. We’ll have a better sense of how much credit conditions have tightened on May 8th when the Federal Reserve releases its Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey. The good news is that lending standards may not have tightened as much as originally feared. The bad news is that standards started to tighten before the March panic emerged, so even a smaller narrowing of the credit spigot would amplify the downside risks facing the economy. As it is, recession odds have been building for some time, thanks to the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate-hiking campaign over the past year. With credit conditions set to tighten further, those odds are now even higher. Indeed, the financial markets fully expect a recession to begin sometime over the second half of this year.

The markets have been wrong before, and many believe that the economy can withstand the credit headwinds coming its way. Although job growth is slowing, the labor market remains tight, with unemployment hovering near record lows and wages still rising at a steady pace. As long as households have a paycheck coming in, they should continue spending and put a floor under the economy. But as job growth slows and recession fears command more headlines, households are likely to save a larger portion of those paychecks to build up precautionary savings. Slower consumer spending, in turn, translates into lower profits, reduced investment spending and eventually more layoffs, setting the stage for an economic downturn.

Hopefully, the widely expected recession will be mild given the economy’s firm underpinnings, including healthy household and business balance sheets, and a labor market that should not deteriorate sharply in the wake of severe worker shortages over the past two years. However, even as one crisis has been avoided, another shock lurks in the wings that could turn a mild recession into a deeper one. Notably, the rhetoric around the looming debt ceiling has not been encouraging, and the risks of a nasty fight, a temporary breach in which the government can’t pay its bills on time, or a sudden shift towards fiscal austerity are increasing. If the debt ceiling imbroglio is not resolved in coming weeks, an economy that is already weakening would endure another confidence shattering blow on both Wall Street and Main Street that would inflict far more damage than is currently expected.

A Nasty Fight

There are few guarantees in life, but a nasty fight over the debt ceiling seems to be one that pops up all too frequently. Depending on the strength of tax revenues in April, the government will run out of funds to pay its obligations, perhaps as early as June, if Congress does not increase the debt ceiling. Negotiations between the parties are usually tense and often not resolved until the last minute. With the political landscape so polarized now, the tension is especially acute; the prospect of a first-ever default is weighing on the financial markets.

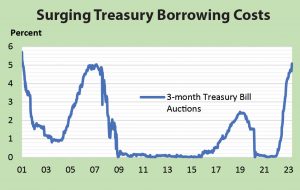

Indeed, traders are already taking notice of the enormous divide between Democrats and Republicans, driving up the Treasury’s borrowing costs. The Treasury Department’s auction of Treasury bills on April 18th produced the highest yield since 2001. As the debt-ceiling deadline draws closer, Treasury bill rates will continue to rise, similar to the pattern seen leading up to past battles on this issue. Unsurprisingly, credit default swaps – reflecting market expectations that the Treasury will default on its debt – have also jumped recently and are higher than the rates seen during any of the debt ceiling debates over the past 15 years.

House Speaker Kevin McCarthy recently offered a proposal to raise the debt ceiling for a year, which includes the provision that non-defense spending be kept at 2022 levels. This is a nonstarter for Democrats, which sets the stage for a protracted battle, but also raises the odds of a sudden shift to fiscal austerity similar to the one that occurred during the Obama administration. According to several respected research studies of the period, that shift posed a significant drag on the recovery that followed the Great Recession, shaving about 2 percentage points from the growth rate between 2010 and 2014.

Will the Fed Blink?

Officially, the Federal Reserve stays away from battles involving fiscal policy, asserting that such issues should remain the purview of Congress and the administration. On paper, therefore, its policies are shaped solely by events over which it has direct control, most notably using its tools to achieve price stability and maximum employment. Over the past year, its focus has been on reducing inflation, pursuing the most aggressive rate-hiking campaign since the early 1980s. Despite its efforts, inflation has only grudgingly receded, while the economy has until recently remained resilient in the face of surging interest rates.

While the effects are starting to filter through more visibly – consumer spending is slowing and other indicators point to weakening growth momentum – the job market is still too hot for the Fed’s comfort, providing it with leeway to hike rates again at the May 3rd policy meeting. While job growth has slowed, conditions in the labor market remain historically tight, with unemployment hovering near 50-year lows and wages rising at a much faster pace than is consistent with the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target.

But the job market is usually the last shoe to drop when the broader economy is weakening. That’s one reason it is hard to detect when a recession gets underway, as businesses tend to hold on to workers – and even keep expanding staff – until it becomes clear that the weakening in revenues and profits is enduring. Because of the acute labor shortages during the post-pandemic recovery, many companies are hoarding workers out of concern that they may not be able to find enough job applicants during the next recovery. That, in turn, creates a sense of artificial strength which is vulnerable to a collapse when the economy’s underpinnings start to crumble. Importantly, it also may prolong the Fed’s tightening campaign beyond the point it is needed, sending the economy into a deeper recession than would otherwise be the case.

Trillion Dollar Question

To be sure, Fed officials are aware of the lagged effects of its rate hikes and wary of overshooting tightness. Some already favor a pause to assess the impact of past increases, although they are still outweighed by the inflation hawks who are concerned about sticky price increases, particularly for services. That said, there is a growing consensus that the next rate increase, whether it is in May or June, will be the last. The question is, what happens next? The official stance of the Fed is that rates will be kept “higher for longer” than the markets expect until inflation is brought under control. But the markets firmly disagree, pricing in a series of rate cuts beginning after the next increase.

Historically, the median time between the final rate increase and first rate reduction has been 4 months. That would be consistent with market expectations, which sees the Fed cutting rates before the end of the year. Unsurprisingly, investors also believe the rate cuts will be taken in response to the recession they see unfolding. That forecast has a good deal of support in recent data. While the economy notched a decent growth rate in the first quarter, all the strength occurred in January. The monthly data for February and March cooled significantly, including consumer spending – which is the main growth driver.

Would the Fed keep rates high if the economy stalls or enters a mild recession? That’s the trillion dollar question dividing the financial markets and the official Fed strategy of keeping rates elevated. According to the quarterly economic projections unveiled at the March 21-22 policy meeting, the Fed expects a recession over the last half of the year, with unemployment rising from the current 3.5 percent to 4.6 percent. The rate has never risen that much outside of a recession, but a 4.6 percent rate would still be lower than the peak rate reached in every previous recession.

Ungluing Sticky Inflation

By all accounts, therefore, the Fed appears willing to accept a mild recession if that’s what it takes to bring inflation to heel. But what if inflation only recedes to, say, 3 percent instead of its long-standing target of 2 percent while the economy continues to contract? Some believe that the Fed should raise its inflation target, thinking that 3 percent is tolerable if the alternative is a deeper recession. However, that would open a can of worms, making it easier for the Fed to conveniently adjust its targets in the future to avoid painful consequences. If nothing else, that would undermine the central bank’s credibility, making monetary policy a less potent weapon in the Fed’s toolbox.

Hopefully, the Fed will not have to deal with that Hobson’s choice. True, getting inflation down from a peak of 9 percent last June to the current 5 percent was the easy part, helped by the clearing up of supply chain snarls, falling oil prices and weaker demand for goods as home lockdowns ended. Getting it from 5 percent to 2 percent will be more difficult, as curbing sticky service prices requires a cooling off of housing and labor costs, the two biggest drivers of service prices.

Happily, there are signs that these hurdles can be overcome. Market rents are already coming down in many regions, thanks to a huge supply of apartment buildings saturating the market. Meanwhile, the labor shortage that’s been driving up wages is easing. For sure, the ongoing wave of retirements linked to an aging population will continue to depress the participation rate of people in the labor force. But getting workers in their prime working age – those in the 25-54 age group – off the sidelines has been a major chore, and key to alleviating labor shortages. That hurdle has been overcome, as the participation rate of this group has finally returned to its pre-pandemic level.

Filling open positions is still a major headache for many companies, but that too is becoming easier as job openings have receded in recent months. As the historically wide gap between openings and jobseekers continues to narrow, pressure on wages should also ease, making the Fed’s job of curtailing inflation more attainable without having to push rates up further. It will be hard to avoid a recession; once a $20 trillion behemoth, which is the U.S. economy, starts to go downhill, it’s almost impossible for it to stop on a dime. Hopefully, it won’t be pushed off a deep cliff by mismanaged negotiations over the debt ceiling.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |