Why Are Economists So Glum?

Economists are often called dismal scientists, as they are more likely to see the proverbial glass as half empty than half full. That label is vividly on display now, as the forecast of a recession within the economic community is more pronounced than ever. In its May survey, the consensus of Blue Chip economists predict a 61 percent chance of recession this year, and even the Federal Reserve’s staff of economists expects a downturn in the second half. These gloomy forecasts are echoed in the financial markets, where investors are pricing in a high probability of a downturn before the end of the year. Simply put, if a recession is coming, it would be one of the most advertised on record.

Most Americans, in contrast, tend to be more upbeat about the economy – at least until adversity strikes home or they are confronted by a shock that threatens to undercut their well-being. The pandemic certainly qualified as a such a shock as it abruptly ended the longest expansion on record and sent 22 million workers to the unemployment lines within two short months. But the economy has enjoyed a remarkable recovery since that COVID shock in the spring of 2020. All the lost jobs have been recovered and then some, household balance sheets are in good shape, jobs and wages are increasing and consumers are spending freely again on experiences and other activities denied them during the pandemic.

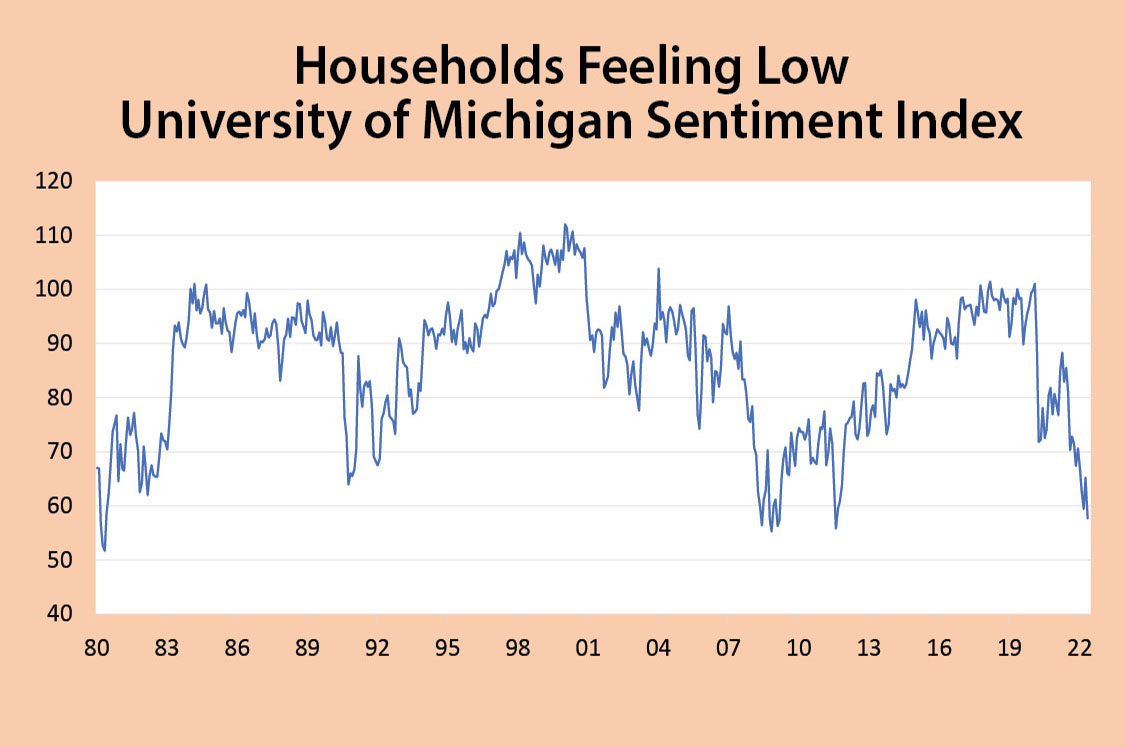

Yet the denizens of Main Street are just as downbeat as economists. Confidence measures have been sinking for months and some are as low as they were during the 2008 financial crisis. The good news is that people do not always behave as they feel, as evidenced by the resilience of consumer spending this year. The bad news is that the longer households retain a downbeat sentiment, the more likely it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. From a macro lens, that means zipping up wallets and purses to build up precautionary savings as a buffer against adversity. Since consumer spending accounts for two thirds of total economic activity, the direction it takes can turn recession fears into a reality.

What’s the Beef?

As noted, households would seem to have more reasons to celebrate than complain. The job market continues to run in high gear, generating 285 hundred thousand payrolls a month over the first four months of the year. That’s a downshift from 2022, when the pace of job growth averaged 400 thousand, but well above the pre-pandemic trend; it is also far stronger than the 100 thousand average monthly growth in the working-age population, driving the unemployment rate down to 3.4 percent. The jobless rate has not been lower in more than sixty years.

With paychecks still flowing in and workers getting sizeable wage increases, it’s hard to see consumers going into hibernation. For a while, it seemed that would be the case, as retail sales fell in February and March after a warm-weather-induced spike in January. But shoppers returned in April, as retail sales rose 0.4 percent. What’s more, the component that feeds into GDP – the so-called control group of sales – staged a robust 0.7 percent gain, lifting it above the average for the first quarter. Hence, the spring quarter started with some momentum, pointing to a likely increase for personal consumption during the April-June period. If a recession is in the cards, as widely expected, it won’t begin at least until the second half of the year as downturns rarely occur when two-thirds of the economy is still expanding.

So why are households so worried? For one, they are constantly bombarded with bad news that cast a harsh spotlight on the economy’s prospects. The debt ceiling crisis in late May generated blaring headlines signaling a doomsday outcome if the Treasury defaults on its obligations for the first time in history. For another, while consumers are still spending, they are also getting less bang for the buck, as inflation is taking more of the dollars spent. Finally, the cost of borrowing has surged, thanks to the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes since early last year, including the last quarter-point increase in May. Not only is that discouraging new purchases, but monthly payments on variable rate loans, such as on credit card balances, have become overly burdensome on a growing swath of the population. Credit card delinquencies are rising, particularly among young adults, who are the fastest growing group of borrowers.

No Help From the Fed

Assuming the debt-ceiling saga is resolved, the other headwinds will not vanish anytime soon. Some relief would be forthcoming if the central bank reversed course from its muscular rate-hiking campaign. Since March of last year, the Fed has lifted short-term rates in 10 consecutive policy meetings for a total of 5.25 percentage points – the most aggressive tightening of policy since the early 1980s – to wrestle down inflation.

Investors widely believe that the hiking campaign ended in May and rate cuts are on the way, starting sometime before the end of the year. The Fed, however, is pushing back, indicating that it may hit the pause button at the June meeting, but is far from pivoting towards rate cuts. Fed Chair Powell and his colleagues have repeatedly said that they intend to keep rates elevated longer than traders in the financial markets expect. The reason: inflation is still too high, underpinned by a resilient job market, and reducing it to the 2 percent target is taking longer than hoped.

With the Fed planning to keep its foot on the brakes, the economy would have a tough road to navigate. On the surface, things look reasonably okay. But under the hood, cracks are showing. As noted, consumers are keeping their wallets open, but they are trading down, substituting less expensive for higher-priced goods whenever possible. The growing resistance towards higher prices reflect the shrinking purchasing power of consumers. Households were much more accepting of price increases in 2021 and 2022 believing they were justified by product shortages. Fortified with enormous government stimulus payments that bloated bank accounts by about $3 trillion together with torrid job and sturdy wage gains, households readily accepted the higher prices without too much pain. But those halcyon days are waning.

High Rates and Shrinking Credit

One reason the Fed may refrain from raising rates again at the June 14 policy meeting is to buy time to assess the impact that past increases are having. Keep in mind that incoming data provide a picture of the economy in the rearview mirror. But monetary policy affects the economy with long and variable lags. Those lags are getting shorter and showing up in real-time transactions. For example, auto sales have been riding the coat tails of pent-up demand during the pandemic when chip shortages emptied dealer lots of inventory. Now supplies are increasing, but their higher prices together with steep financing costs are pinching demand. In the first quarter of 2023, the average monthly payment for a new car rose to $736 from $585 two years earlier.

The poster child for an industry victimized by higher interest rates is housing, and the surge in mortgage rates to 7 percent late last year from under 3 percent in 2020 clobbered home sales and stifled refinancing activity. Mortgage rates have since receded somewhat, but the damage is done. Prior to COVID, existing home sales – which account for 80 percent of total home sales – were running at a 5.5 million annual rate. Currently, they are languishing at a 4-4.2 million pace. Not only have high mortgage rates and home prices pushed prospective home buyers to the sidelines, but homeowners are also not putting their property on the market because they are locked in with the low rates obtained years earlier when the homes were originally purchased.

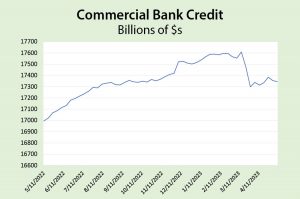

Finally, the Fed’s aggressive rate-hiking campaign is not only deterring demand, but also crimping the supply of credit. The recent panic that saw three regional bank failures has been contained, but lenders have toughened credit standards, depriving wide swaths of borrowers of much needed funds. Indeed, bank credit suffered its biggest contraction on record following the banking turmoil that erupted in March. Reduced credit availability has the same growth-retarding effect as a rate hike, which is another reason the Fed may decide to pause at its June policy meeting.

Big Toll on Small Businesses

The most harmful effects of reduced credit availability are falling on small businesses. Mom and pop establishments do not garner headlines, but they are the biggest generators of jobs in the economy. In fact, small businesses accounted for all the net job growth between February 2020 and the end of 2022. While heavy layoffs at high-profile tech firms are getting all the attention, the closing of the credit spigot for small firms is spurring an even greater surge of firings among these establishments. Labor Department data reveal that firms with 1-9 workers laid off or fired 341,000 workers in March, more than twice as many as in February. Unsurprisingly, small business sentiment is sinking fast.

According to the latest survey by the National Association of Independent Businesses, small business optimism is the lowest in more than a decade, with respondents citing restrictive credit availability and high borrowing costs as the principal sources of angst. Throughout most of the post-COVID recovery, labor shortages topped the list of worries for small businesses, reflecting how dramatically the times are changing. If small firms can’t borrow, they can’t meet payroll, indicating that labor demand, not supply, will pose more of a threat to the economy going forward.

Simply put, the glum mood of households and small businesses is beginning to affect behavior, making the outlook look more ominous than portrayed by incoming data. The Fed still clings to the hope that it can wrestle down inflation without causing a big spike in unemployment – achieving the so-called “soft landing.” So far, so good, as the downbeat sentiment of households and businesses hasn’t yet tanked the economy. Even the “dismal” economists and bearish investors are pushing back the timing of the expected recession, primarily reflecting the resilience of consumers. But that very resilience along with the still tight labor market is keeping inflation higher than the Fed is willing to tolerate. The question is, how much of an economic slowdown is the Fed willing to accept to get inflation down to its 2 percent target? It’s hard to see or feel what everyone’s worried about now, but that’s probably the most worrisome element for the Fed to consider.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |