Will This Time Be Different?

Contrary to revised expectations – and robust economic data – the business cycle has not been repealed. Yes, a recession is coming, but it is taking an awfully long time to arrive. When it does, its shape may look different, more like a mini recession than an outright downturn. This would be akin to a soft landing – a mild slide in output accompanied by a few job losses. But if the weakness is pervasive and lasts more than a few months, it will nonetheless be labeled a recession by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the unofficial arbiter of when a business cycle starts and ends.

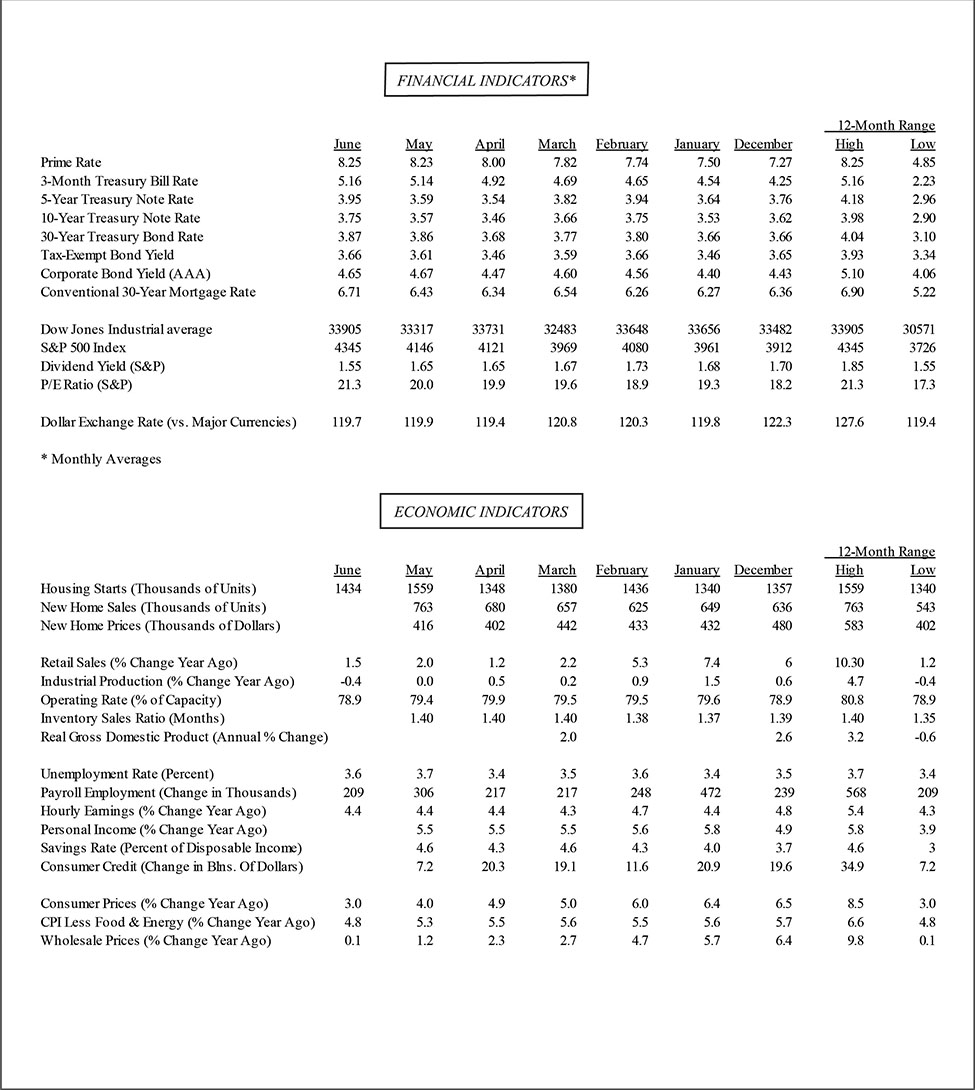

But what’s in a name? If such a Goldilocks outcome materializes and inflation is brought to heel, the Federal Reserve will gladly take it. Indeed, policymakers have been scratching their heads for some time over why the economy hasn’t yet succumbed to the most aggressive rate-hiking campaign since the 1980s aimed at taming inflation. Following more than 5 percentage points of rate increases since March of last year, the economy’s growth engine has sputtered, but not stalled. In fact, growth was revised up significantly in the first quarter of this year – from 1.3 percent to 2.0 percent – and tracking models indicate that GDP staged a similar increase in the second quarter.

While many fret that the economy is undergoing a Wile E. Coyote moment – suspended in thin air and poised for a sudden and steep drop – the skeptics of the economy’s staying power are losing advocates. Earlier this year, particularly after the banking turmoil that saw the collapse of some regional banks, expectations that a recession was just around the corner ran high. Investors priced in a near 100 percent chance of a downturn this year, and the consensus of economists was equally convinced it would occur. Now, not so much. One reason: inflation is receding more rapidly than thought, even as the economy’s underpinnings – most notably the job market, retains considerable firepower. To many, that means the Fed can ease up on the monetary brakes, removing one headwind that is the most likely to push the economy over the cliff. Is this wishful thinking? We’ll see. It would be a historic breakthrough for monetary policy, which has usually overshot the mark in its quest to rein in inflation. But it’s also rare to see a sustained decline in inflation amid a historically tight labor market and sturdy growth. We are rooting for Goldilocks, but still fear the wolf.

Still Chugging Along

Earlier in the year, most thought the economy would be on the cusp of, if not in, a recession by now. Clearly, it is not. Despite the run-up in borrowing costs engineered by the Federal Reserve, tougher lending standards enforced by banks since the 9-day turmoil last March, and, until recently, slumping household confidence, consumer spending has continued to keep the economy afloat. Retail sales did slow in June to a slim 0.2 percent gain, but from a robust 0.5 percent increase in May that was revised up from an initial estimate of 0.3 percent. The bad news is that inflation rose by the same amount, so real purchases were unchanged. The good news is that the higher prices did not discourage spending, as consumers had the wherewithal to purchase the more expensive goods.

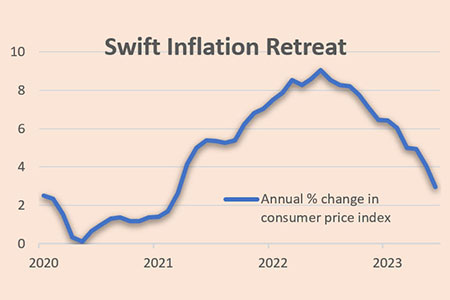

With most data for June now in the books, the economy appears to have recorded a decent growth rate in the second quarter, rivaling the 2 percent pace in the first. That not only puts it above recessionary waters, but it’s also about equal to the average growth rate during the ten-year pre-pandemic expansion. Does the stubborn resilience of the economy mean that the Fed’s aggressive rate hikes failed to do the job? Not if you look at the main objective of its mission – bringing down inflation. In fact, you could say it is ahead of schedule. It took 16 months for inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, to surge from under 3 percent to over 9 percent, but only 12 months to drop from over 9 percent back to under 3 percent.

Of course, this dramatic turnaround does not truly describe what happened to inflation, as the headline boomerang masks stickier prices for much of the goods and services people buy. Economists and policymakers like to exclude items whose prices are volatile to better understand the underlying inflation trend. This exercise paints an improving, but less impressive disinflationary picture. The so-called core CPI, which excludes food and energy items, slowed to 4.8 percent from a peak of 6.6 percent last September, and prices for services – which are still in heavy demand – are rising at a 6.5 percent annual rate, down from an 8 percent peak in January.

More Work to Do

While these inflation measures are improving, they are all still well above the Fed’s 2 percent target, suggesting that the central bank has more work to do to finish the job. Many feel that the easy pickings are over and the last mile to the finish line will be a much harder slog. That’s particularly so if the economy remains as muscular as it is and generating hefty wage increases that businesses are pressured to pass on to consumers. But this may be a simplistic way of looking at the issue. After all, inflation has steadily receded even as the economy continued to grow amid a historically tight job market. Why take away the champagne if the party is keeping everyone happy?

That, of course, is where the rubber meets the road. The Fed understandably believes that inflation fell despite that unforgiving backdrop because the special pandemic-era forces that propelled prices higher have unwound and punctured the inflation balloon. Supply bottlenecks that created product shortages have mostly cleared, the energy price spike from the Ukraine war shock has unwound and the lockdown-related surge in demand for goods has ebbed as the economy reopened, prodding consumers to shift buying preferences away from physical goods to experiences. The normalization of consumer spending is still underway.

Hence, the Fed is now striving to correct traditional demand and supply imbalances that it believes is keeping a floor under inflation. Most notably, it wants to tame demand to bring it more in line with the economy’s output potential, and to restrain job growth to bring it more in balance with the increase in labor supply. The two, of course, go hand-in-hand. By curbing demand, business revenues would suffer, and employers would likely respond by reducing labor costs – the largest expense on most balance sheets – through cuts in hiring. As the job market turns weaker, so too would worker bargaining position, curbing wage demands and the pressure on employers to raise prices.

Misplaced Target?

But the argument that sustaining the disinflationary trend requires more policy tightening to squeeze businesses and labor is not overly compelling. True, rising wages puts pressure on employers to raise prices. This is most evident in the service sector that is more labor intensive than the goods sector, which can rely more on productivity to offset labor costs. A barber can only cut one head of hair at a time, but a new machine in a factory equipped with the latest technology can increase a worker’s output – or replace the worker. (The actors strike was stoked by fears of AI replicating the image of an actor – and technology may soon do the same in the service sector).

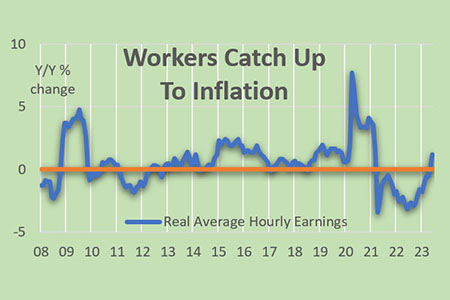

But it’s unclear how much blame for inflation should be attributed to labor costs. It is true that wage gains have finally caught up with inflation, at least by one measure of average hourly earnings compiled by the Labor Department. But rather than leading inflation higher – the causal input that the Fed worries about – worker pay has lagged inflation for more than two years, the longest stretch in which workers lost purchasing power since the late 1980s. That was also the last time the Federal Reserve lifted its policy rate into double digits, both to tame inflation and check inflation expectations by workers.

This time, workers have not increased wage demands in anticipation of higher inflation but to make up for more than two years of lost purchasing power. In fact, inflation expectations have remained well anchored throughout – so it is fair to say that wages have followed inflation, not the other way around. Hence, as inflation continues to gradually recede, so too will wage gains, hopefully at the same or slower pace so that workers would retain the purchasing power they recaptured. Not only would a recession induced by an overly restrictive Fed policy throw millions of workers out of jobs – and reverse the pay gains they achieved – it would primarily victimize lower-paid jobholders and undo the reduction in income inequality brought on by a robust job market.

Lots of Drag in the Pipeline

When the Fed decided to keep rates steady at its June policy meeting, following ten consecutive increases, it did so partly to assess the impact that past rate hikes were having. In the month since then, not much has changed with the economy, as job growth and consumer spending have both held up well. While headline inflation, as noted, has fallen significantly, prices on a broad list of services have remained sticky – hence the Fed chose to raise rates by 0.25% at the July 25-26 policy meeting.

At the same time, many expect that the increase will be the last of the tightening cycle, which has underpinned the growing sentiment that the economy can avoid a recession. No doubt, a move to the sidelines would increase the odds the economy can stay afloat. We fear, however, that there is enough tightening in the pipeline to push the economy into a downturn. It’s important to remember that monetary policy affects the economy with long and variable lags, and the lagged impact has yet to play out. Most of the strong data the Fed is looking at is either backward looking or driven by forces that are poised to weaken.

Indeed, a host of time-honored leading indicators is pointing to a recession, including the Conference Board’s leading economic index, a deeply inverted yield curve, and low consumer expectations of economic conditions and buying plans. Home sales, which are always the first to succumb to a recession, are being clobbered by high mortgage rates. Some believe that “this time will be different” because of the unusual pandemic-related forces behind the current business cycle. That reasoning has been invoked many times in the past, but has never worked out. Recessions come and go for a variety of reasons and it is hard to believe that this time would be any different.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |