The Great Divide Between Feelings And Behavior

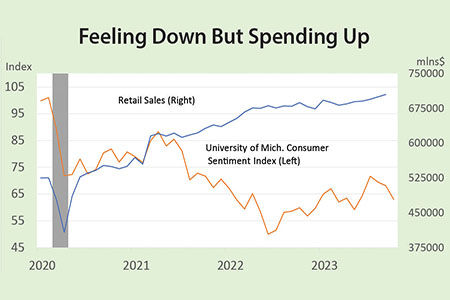

The American public may not be feeling better about things, but economists clearly are. Most households think the economy is going in the wrong direction, and consumer confidence in one prominent survey is currently at recession levels. To be sure, there is a heavy political component in many of the surveys. Democrats, for example, are far more upbeat than Republicans regarding the health of the economy, but that sentiment is flipped on its head when Republicans occupy the White House. While economists are also influenced by political beliefs, they presumably rely on hard data and are more objective when presenting their outlooks.

Until recently, economists and the public were more in sync about future prospects. Both believed that a recession was just around the corner, although economists were never as downbeat as the public regarding current conditions. Now, not so much. The latest quarterly poll by the Wall Street Journal reveals that more than 50 percent of economists believe a recession will be avoided, the first time in over a year that a majority felt that way. Recency bias may be at play here. The economy has performed far better than economists thought, inflation is coming down, and the Fed is signaling that it may be done raising interest rates. This fortuitous combination of events in the face of powerful headwinds suggests that the economy has more staying power than generally believed; it also suggests that the Fed may be close to declaring “mission accomplished” in its efforts to conquer inflation without spurring a big increase in unemployment, something that most economists thought impossible until recently.

Clearly, the odds that the economy will stay afloat at least through the end of this year have increased. Consumers, the main growth driver, are keeping their wallets wide open as evidenced by the blockbuster retail sales report for September and the upwardly revised sales for July and August. Not only does that translate into a blistering 8.4 percent increase in sales for the third quarter, it also means that consumers are heading into the fourth quarter with considerable momentum. It would take a lot to tip a $22 trillion economy into a recession before 2024, and its ongoing strength in the face of still elevated inflation increases pressure on the Fed to raise rates again. However, the full effects of past increases have yet to ripple through the economy and there’s a better than even chance that they, along with other stiffening headwinds, will cause the growth engine to downshift, if not stall out by early next year.

Consumers Keep On Spending

Despite the gloom and doom sounded by households, they are still spending freely. If the gangbuster retail sales report for September is any indication, they are not just buying essentials but going on a spending binge, flocking to restaurants and bars at a breakneck pace. This is not the behavior of people who believe a recession is either here or just around the corner. Granted, it is not uncommon for households to act differently from what they feel – or express in polls. But the discrepancy this time is particularly wide.

If a recession is to be avoided, consumers must keep spending, since they account for roughly 70 percent of total activity. The question is, why are they spending so much if they feel downtrodden? And how long will this extraordinary behavior continue? As noted, political leanings play a big role in how people feel about conditions – even more so in today’s highly polarized environment. But that may influence the way they vote, not necessarily how they behave. Their willingness to spend or save more will depend on their actual job, income, and wealth conditions, and that’s what most economists rely on in making their forecasts. These conditions, in turn, are portraying a far more upbeat picture than what households believe to be the case.

If a recession is to be avoided, consumers must keep spending, since they account for roughly 70 percent of total activity. The question is, why are they spending so much if they feel downtrodden? And how long will this extraordinary behavior continue? As noted, political leanings play a big role in how people feel about conditions – even more so in today’s highly polarized environment. But that may influence the way they vote, not necessarily how they behave. Their willingness to spend or save more will depend on their actual job, income, and wealth conditions, and that’s what most economists rely on in making their forecasts. These conditions, in turn, are portraying a far more upbeat picture than what households believe to be the case.

Simply put, consumers are in much better shape than economists expected. Recent revisions made by government statisticians reveal that households had more income over the past three years, and, importantly, a much larger cushion of savings than previously thought. The government doled out $5.1 trillion in pandemic-related support payments even as households were locked in for most of 2020, and, hence, unable or unwilling to spend a big chunk of those funds, particularly for social experiences that heightened health risks. However, economists thought that most of those savings were depleted early this year, leaving consumers with much less firepower to sustain spending. Apparently, that was not the case.

A Bulge In Wealth

The latest Survey of Consumer Finances by the Federal Reserve, considered to be the gold standard that measure household financial conditions, provides a striking illustration of the financial muscle built up by Americans during the pandemic. Indeed, virtually all segments of the population, whether by race, demographics, or income brackets, became far richer by the end of the pandemic in 2022 than they were in 2019. A summary statistic says it all: fueled by rising house and stock prices, median net worth of all households jumped by an astonishing 37 percent after adjusting for inflation, the largest increase since the survey was first taken in 1989.

Importantly, lower income households and minorities enjoyed the biggest percentage climb. That’s significant for the economy because this segment of the population spends a larger fraction of their income and wealth than upper income households who tend to save more. Even so, they used a big part of their newfound wealth to pay down debt and strengthen their financial condition. Debt repayments as a share of median incomes fell to 13.4 percent in 2022, also the lowest on record. While a strong rebound in job creation contributed to the vast improvement in household balance sheets, most of the income gains during the period was wiped away by inflation, which no doubt factors into the gloomy mindset of households.

Along with appreciating home and stock prices, the surge in net worth benefited immensely from the generous pandemic-linked support from policymakers. The enormous help from Washington, reinforced by the turbo-charged easy monetary policy that poured free money into the economy, is a far cry from the relatively tepid government response following the Great Recession and financial crisis in 2008. Then, politics prevented more generous fiscal support and households were stuck with heavy mortgage debt burdens that took years to work off, constraining consumer demand during most of the 2010s.

The Employment/Inflation Tradeoff

An ongoing debate is whether policymakers were overly aggressive in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing to the untenable inflation environment that is now the number one domestic scourge in the minds of households. This is the flip side of the debate over the response to the 2008 Great Recession, which is now considered to have been overly restrained. While the tamer response then kept inflation in check, it took 6 1/2 years to restore the job losses incurred during that downturn, and the unemployment rate remained over 5 percent for six years. In contrast, unemployment has currently remained under 4 percent for 16 consecutive months and still counting, something not seen since the 1960s, and all the jobs lost during the pandemic were recovered in just over two years.

Achieving the right balance between unemployment and inflation is a long-standing challenge of policymakers. Not only is that inflection point very difficult to identify, but it is also a moving target. In the past, a 5 percent unemployment rate was viewed as consistent with stable inflation, a rate that would be totally unacceptable now. That said, it is generally accepted that lower unemployment is associated with higher inflation and vice versa. That’s why the Federal Reserve still clings to the notion that wrestling inflation down to its 2 percent target can only be accomplished by a weaker job market.

Achieving the right balance between unemployment and inflation is a long-standing challenge of policymakers. Not only is that inflection point very difficult to identify, but it is also a moving target. In the past, a 5 percent unemployment rate was viewed as consistent with stable inflation, a rate that would be totally unacceptable now. That said, it is generally accepted that lower unemployment is associated with higher inflation and vice versa. That’s why the Federal Reserve still clings to the notion that wrestling inflation down to its 2 percent target can only be accomplished by a weaker job market.

In recent comments, Fed Chair Powell and other Fed officials have questioned whether monetary policy is sufficiently tight, despite the aggressive rate hikes over the past 19 months, if the job market continues to be as strong as it is. After all, if jobs are plentiful and generating hefty paychecks, workers would be more willing to accept higher prices, and companies would feel empowered to raise them. The Fed needs to short-circuit that link and believes that a softer job market is the only way to accomplish that.

Weakening Signs

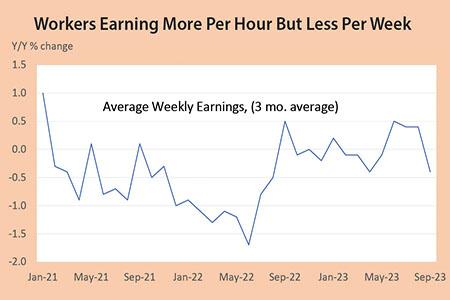

To the Fed’s dismay, however, job growth has picked up in recent months, with employers adding an average of 266,000 workers a month during the third quarter, including 326,000 in September, up from 201,000 in the second quarter. In the eyes of the Fed, this growth in paychecks provides households with more spending power, and, perhaps, the ability to withstand further price increases. While policymakers may refrain from hiking rates again, preferring to wait and see how past increases play out, the sustained strength in job growth at least bolsters their announced intention to keep rates “higher for longer.”

Clearly, the resilient job market alongside robust consumer spending underpins the heightened optimism of economists that a recession can be avoided. However, the surprising strength we have been seeing is based on backward looking data through September, and market interest rates have since risen by another half-percent. Cracks in the economy are beginning to open up. The housing market is being clobbered by mortgage rates around 8 percent, auto loan delinquencies are at record levels, and banks are stiffening lending standards, particularly for consumer loans.

Importantly, some of the data are not as strong as they seem on the surface. While job growth has accelerated, workers are putting in fewer hours, so the growth in weekly earnings fell in September. The surge in net worth may have strengthened balance sheets, but consumers cannot easily spend their housing wealth or liquidate stock holdings without incurring a sizeable tax bill. Hence, they drew heavily on savings to finance spending, and the savings rate is now well below pre-pandemic levels. Simply put, the financial muscle driving the economy’s growth engine is weakening, and households may soon behave more as they feel. When that happens, the economic community will be far less optimistic that a recession can be avoided.

Importantly, some of the data are not as strong as they seem on the surface. While job growth has accelerated, workers are putting in fewer hours, so the growth in weekly earnings fell in September. The surge in net worth may have strengthened balance sheets, but consumers cannot easily spend their housing wealth or liquidate stock holdings without incurring a sizeable tax bill. Hence, they drew heavily on savings to finance spending, and the savings rate is now well below pre-pandemic levels. Simply put, the financial muscle driving the economy’s growth engine is weakening, and households may soon behave more as they feel. When that happens, the economic community will be far less optimistic that a recession can be avoided.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |