Higher Speed Limit Slows Inflation

The holiday shopping season has officially kicked off, and while some have predicted a less festive Santa might have been coming down the chimney, the nation’s collective stockings will not be filled with coal. Consumers have not yet zipped up their wallets and purses, but they are running out of the fuel that pumped-up spending last year and the year before. Job growth is slowing, the pandemic-era excess savings are mostly depleted, banks are tightening credit, student loan payments have restarted, and borrowing costs have spiked.

We have noted in the past that the downbeat mood of households does not always translate into weaker spending decisions. That divergence was strikingly evident in the third quarter, when consumers went on a veritable spending binge despite expressing deep dissatisfaction with the economy’s direction. In October, however, they behaved more like they felt, as retail sales fell for the first time since March. The National Retail Federation expects holiday sales in November and December to rise by 3-4 percent from last year, weaker than the 5.4 percent gain in 2022 and the blistering 12.7 percent in 2021.

The good news is that consumers are getting some relief on the inflation front. Retail inflation plunged from 9.1 percent in March 2022 to just over 3 percent this October, the most pronounced decline outside of a recession since the early 1950s. Wage growth is also slowing, but not as rapidly, so paychecks are going a longer way. That, in turn, should keep a floor under spending, and perhaps, stave off a recession. But the Federal Reserve believes wages are still growing too fast and is the main hurdle preventing inflation from retreating to its 2 percent target. The risk is that the central bank will keep interest rates higher for too long, bringing on an unnecessary recession. Hopefully, the Fed does not shape policy decisions on an unrealistic timetable. By the time wage growth does slow enough, it may be too late for the Fed to start cutting rates to ward off a recession.

Higher Speed Limit

The financial markets have been on a tear since early November when the Fed decided to keep its key policy rate unchanged for the third consecutive rate-setting meeting. Whether that means the rate-hiking campaign is over remains to be seen. The Fed did not change its forecast of one more increase it predicted over the summer. But recent comments by Chair Powell, as well as many of his colleagues strongly suggest that the final hike is now in the rearview mirror unless the inflation decline stalls out, or worse, reverses.

The most interesting aspect of the Fed’s decision to put rate hikes on hold is that it comes on the heels of a gangbuster growth rate for the economy, as GDP surged by an eye-opening 4.9 percent annual rate in the third quarter, the strongest since 2021, and way above the economy’s potential growth rate of roundly 2 percent. Historically, when the economy grows faster than its output capacity, inflationary pressures increase and spurs the Fed into demand-curbing rate hikes. That backdrop stoked the inflation surge in 2021 and 2022 when trillions of dollars in stimulus payments boosted demand while global supply constraints suppressed output. Although demand is slowing now, consumer inflation expectations are rising, and actual inflation remains higher than the Fed’s 2 percent target. So, what’s behind the Fed’s newfound patience?

The answer is that the Fed thinks the economy has undergone a significant transformation that allows inflation to continue to recede even if growth exceeds its long-term trend. Indeed, that’s precisely what occurred in the third quarter when, to the surprise of many, torrid growth did not prevent inflation from falling. Simply put, the economy’s potential growth rate – its speed limit – also ratcheted up, more than matching the surge in demand. That’s because the supply constraints that restrained output and growth is unraveling: labor shortages eased as people returned to the workforce, bottlenecks cleared up easing product shortages, and productivity increased. These conditions remain in place and could well act as a brake on inflation for a while longer.

Soft Landing Hopes Improve

The recognition that the economy’s increased growth potential could suppress inflation is a striking about-face by the Fed. Until recently, policy makers thought that only a severe cutback in growth and, by extension a weaker job market, would bring inflation down. Although not explicitly stated, it was generally assumed that Fed officials would accept a recession as collateral damage in the anti-inflation fight, with the hope that any downturn would be mild. The Fed was not alone in this thinking, as Wall Street and most economists looked at the historical record of Fed tightening cycles and were just as convinced that a downturn was inevitable, particularly given how aggressively rates were driven up since March 2022.

The recognition that the economy’s increased growth potential could suppress inflation is a striking about-face by the Fed. Until recently, policy makers thought that only a severe cutback in growth and, by extension a weaker job market, would bring inflation down. Although not explicitly stated, it was generally assumed that Fed officials would accept a recession as collateral damage in the anti-inflation fight, with the hope that any downturn would be mild. The Fed was not alone in this thinking, as Wall Street and most economists looked at the historical record of Fed tightening cycles and were just as convinced that a downturn was inevitable, particularly given how aggressively rates were driven up since March 2022.

However, following a record thirteen consecutive months of declining core inflation, a consensus is forming that the Fed can conquer inflation without causing a recession, thanks in good part to the economy’s expanded output capacity, which allows supply to accommodate a sustained increase in demand. This prospect, known as a soft landing or, more recently, immaculate disinflation, is also gaining acceptance in the financial markets, spurring a strong rally in stock prices and a decline in bond yields. Even the Fed has come around to this thinking, with Chair Powell noting that a recession is no longer the default option. But he also notes that wringing the last mile out of inflation – getting it from 3 percent to 2 percent — will be more of a struggle unless wage increases slow more sharply.

Still, the inflation doves argue that if price increases can be slowed from 9 percent to 3 percent, there is no reason another 1 percent can’t be wrested out of the system without inducing more economic damage than necessary. In their eyes, since the unusual pandemic-related shocks that suppressed output and boosted demand are unwinding, it is only a matter of time before inflation returns to pre-pandemic levels. This group understandably believes that the Fed should start cutting rates soon, before the pain on housing and other rate-sensitive sectors intensifies and sends the broader economy into an avoidable recession.

Patience Not Unlimited

The Fed will most likely keep rates unchanged at its upcoming meeting in mid-December, if only because the disinflationary trend is still firmly in place and most officials want more time to assess how past rate increases are playing out. It is also what investors expect, and the Fed rarely takes moves that would disrupt market conditions unless it wants to send a clear message to change investor expectations. The current message is that it will hold off on another rate increase for now, but it is not even thinking about cutting rates.

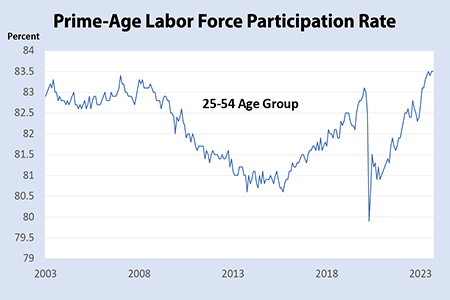

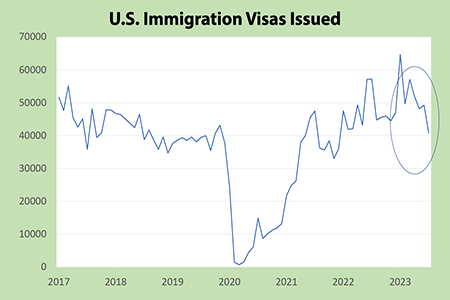

That said, the Fed’s patience in holding rates steady is not open-ended. If the economy and the job market continue to chug along at a faster than normal speed, it is hard to see more of an inflation retreat. After all, the forces that pumped up the economy’s growth potential will not be around much longer. Returning workers and a surge in immigration sparked a rebound in the labor force – relieving worker shortages – but both have reached their limits. The labor force participation rate of prime age workers is above its pre-pandemic peak, and the administration is cracking down on immigration. Indeed, the number of visas issued by the government fell by almost 50 percent over the past six months.

That said, the Fed’s patience in holding rates steady is not open-ended. If the economy and the job market continue to chug along at a faster than normal speed, it is hard to see more of an inflation retreat. After all, the forces that pumped up the economy’s growth potential will not be around much longer. Returning workers and a surge in immigration sparked a rebound in the labor force – relieving worker shortages – but both have reached their limits. The labor force participation rate of prime age workers is above its pre-pandemic peak, and the administration is cracking down on immigration. Indeed, the number of visas issued by the government fell by almost 50 percent over the past six months.

Meanwhile, with few exceptions, supply chains have been fixed and goods are flowing freely to stores and warehouses, where inventories are mostly back to normal. Hence, the production boost aimed at meeting a huge backlog of demand for goods built up during the pandemic no longer exists. What’s more, the cushion of excess capacity that enabled factories to ramp up production to meet demand is virtually gone. In fact, goods producing industries are operating at a higher percentage of capacity now than at the peak of the 2010-2019 expansion.

Meanwhile, with few exceptions, supply chains have been fixed and goods are flowing freely to stores and warehouses, where inventories are mostly back to normal. Hence, the production boost aimed at meeting a huge backlog of demand for goods built up during the pandemic no longer exists. What’s more, the cushion of excess capacity that enabled factories to ramp up production to meet demand is virtually gone. In fact, goods producing industries are operating at a higher percentage of capacity now than at the peak of the 2010-2019 expansion.

Will the Fed Pivot in Time?

Hence, any hope for a soft landing will depend on how well the pilot, namely the Federal Reserve, is able to bring demand more into balance with the economy’s speed limit, which is poised to lose the temporary influences that pumped up its growth over the past year. The challenge is to determine what level of interest rates would bring about that equilibrium and how long to keep it there. To its credit, the Fed hit the pause button in July to gauge the impact previous rate increases are having, recognizing that there are lagged effects which still have not played out.

Many borrowers, for example, are still paying the low rates obtained on loans taken out two or three years ago. The lucky ones are homeowners who locked in those rates for up to 30 years. But people with credit card debt are facing record interest rates on their unpaid balances and delinquencies are rising, particularly among lower-income borrowers. Until recently, pandemic savings helped cover financing costs and were used to pay down a big chunk of outstanding debt. But those savings are mostly depleted while credit card borrowing has ramped up. Meanwhile, the moratorium on student debt repayments has ended, which will further squeeze the budgets of 40 million borrowers.

Hence, the lagged effects of the Fed’s rate hikes over the past 19 months are starting to kick in, and the drag on consumer spending should become more pronounced in coming months. Whether the setback in retail sales in October is an early sign of the impact remains to be seen. It may well be that consumers took a breather after a torrid spending spree in the third quarter. But with savings diminished and borrowing more costly, households will be relying more on jobs and wages to sustain spending. Both are slowing, which should reinforce the unwinding of pandemic shocks to cool off inflation over time.

The risk is that the Fed, which does not see inflation falling to 2 percent until 2026, will keep rates elevated for too long, leading to a hard landing for the economy. The financial markets are currently pricing in Fed rate cuts starting in the spring, far earlier than the timetable set by policymakers. It’s unlikely that inflation will be much closer to 2 percent by then, and Fed officials fear easing policy prematurely before inflation is conquered. The economy may adjust to the higher rate environment and stay afloat, but history indicates that once slowing growth starts to drive up unemployment, it is hard to stop and stave off a recession. Hopefully, the Fed will take its foot off the brake in time to prevent history from repeating itself.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |