No Quit in This Economy

2023 ended on a high note, punctuated by sharp rallies in both the stock and bond markets, tangible evidence that the economy is on a steady disinflationary growth path, and strong indications that the Fed is poised to cut rates in 2024. The soft-landing scenario that most economists and investors scoffed at early last year now seems more likely to play out. This about-face in prospects was strikingly echoed in the financial markets as 2023 drew to a close. Stocks recouped all their losses suffered in 2022 while market yields erased a good part of the surge over the first ten months of 2023. Indeed, an investor in the 10-year Treasury security who went into hibernation at the start of the year and awoke at its end might think that nothing of note occurred over the period. That’s because the yield wound up at the same place it started, completing a round trip journey from 3.88 percent to just over 5 percent in October and back down to 3.88 percent on December 31.

Of course, the year was marked by seismic forces whose reverberations have yet to be determined. Geopolitical tensions escalated, with no end in sight for the war in Ukraine and a conflagration in the Middle East that is widening beyond Gaza. Domestic political shenanigans took center stage for months, as the House Speaker was ousted and most legislation, including debt funding bills, remain in limbo. The failure of several regional banks in the spring heightened recession fears and invoked memories of earlier financial crises. Finally, while the last of eleven central bank rate hikes likely occurred in July, their full effects on the economy have yet to play out, as most household and business borrowers locked in lower rates that prevailed before the tightening campaign got underway in March 2022. A big chunk of those loans will have to be refinanced at prevailing higher rates starting in 2024 or paid down, either of which will be a drag on activity.

As the curtain rises on 2024, it’s highly unlikely that the economy will either fall off a cliff or stage a vigorous rebound in the foreseeable future. A $24 trillion economic behemoth does not change course on a dime, unless some unexpected external shock, such as a pandemic, sends it off the rails. Although activity has held up considerably better than thought a few months ago, a slowing trend should soon begin that is expected to continue throughout the year. Likewise, inflation has fallen far more drastically than anyone, including the Fed, expected; but the disinflationary trend has recently slowed and could run into more resistance in coming months. The biggest uncertainty is policy – particularly fiscal policy – which, given the volatile political dynamics of the past several years, is almost impossible to build into a reasonable forecast.

Wake-Up Reports

Things were going smoothly early last fall as a red-hot economy and job market lost some steam and inflation continued to ease. The Fed paused its rate-hiking campaign in July, believing that the risks between more inflation and higher unemployment were evenly balanced. By December, it became more confident that inflation was under control and predicted that a new cycle of rate reductions would commence in 2024. That sent the markets into a joyous mood, sending stock prices sharply higher and market interest rates lower.

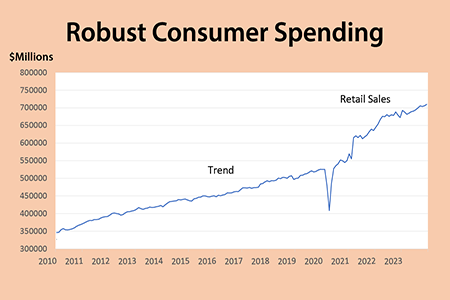

But the best laid plans do not always adhere to the script, as fresh data in January is providing a wake-up call for traders. Instead of continuing on the virtuous path of slowing growth and lower inflation, the economy turned hotter again in December and the inflation retreat stalled. All key indicators for the month – on jobs, consumer prices and household spending – came in stronger than expected. Suddenly, the bets regarding a swift pivot by the Fed towards cutting rates looked less promising. After all, if the data showed that the economy retained more vigor than thought, the last thing it needs is more stimulus to stoke inflation.

Keep in mind that the Fed’s biggest fear is that it would ease up on the brakes prematurely, allowing inflation to reignite in a repeat of the mistakes made in the 1970s. For sure, the overshoots were not particularly alarming, but the financial markets tend to overreact to data surprises, and the response to the January reports was no exception. The biggest toll was felt in the bond market, where yields backed up abruptly in early January, although they remain well below their peaks seen last October.

Should We Be Concerned?

Not yet. It’s a time-honored – but true – adage that one-month does not make a trend, particularly if that month is the final one of the year that contains several important holidays. Things could look quite different in January, which could well jolt investor perceptions again. That said, if the December data holds up upon revisions, it means that the economy had more momentum heading into 2024 than thought. And if activity is starting the new year at a higher level, it imparts an upward bias to growth in the first quarter.

Assuming new data do not reveal an economy falling off a cliff in January, the Fed could be looking at an economy that is still growing above trend in the first quarter at its policy meeting in March. Indeed, if the quarter ends on a strong note and progress on inflation stalls it could even raise interest rates, something that policy makers had not taken off the table at its December meeting. It probably won’t, but it most certainly would not cut rates under those circumstances. In any event, the uncertainty caused by recent data has prompted traders to scale back their bets of a March rate cut that had been so prevalent at the end of last year.

There is a strong case for the Fed to stand pat for a while, at least until May, giving it more time to see if economic activity and inflation are still moving in the right direction. Odds are that the end of year strength in the data reflect more of a hiccup than a change in trend. What’s more, the headlines do not describe a complete picture of unfolding conditions, as there are pockets of weakness under the hood. More jobs were created in December than expected, but companies are listing fewer positions, portending slower hiring in coming months; workers are not job-hopping as much, reflecting less confidence in landing a new one; and while the unemployment rate remains historically low, unemployed workers are taking longer to find a job. Likewise, the consumer price index rose more than expected in December, but volatile gas and auto prices accounted for much of the overshoot. Importantly, consumer inflation expectations are declining, which could have a big influence on spending behavior.

Sticky Service Prices

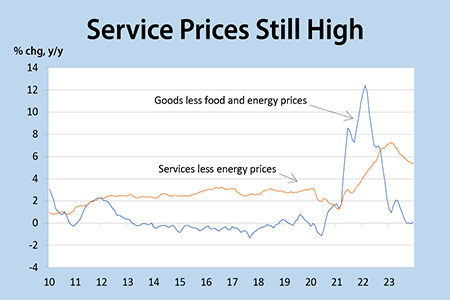

The rapid decline in inflation in 2023 strengthens the case for cutting rates sooner than later, as it reduces the risk of sending the economy into a recession. But the forces behind last year’s disinflation will be less potent this year. True, prices for goods are still easing, thanks to the healing of pandemic-era supply chain disruptions and the shift in consumer buying preferences away from goods towards services. But the healing process has run its course, and the mix of consumer spending has normalized. If anything, goods prices may come under upward pressure from the recent jump in global shipping costs caused by the Houthi attacks on ships in the Red Sea. Still, the decline in inflation for goods has been far more pronounced than for services, and that divergence should continue.

But prices for services, which account for a larger share of consumer purchases, remain a sticky point for the Fed. That was particularly evident in the closing months of 2023, when the gradual slowdown in service price gains hit a wall. Indeed, the so-called supercore inflation index (service prices less housing costs) that the Fed closely watches was still running at a 6 percent annual rate over the final three months of last year. Unless service price gains ease more rapidly, the Fed will have a hard time wrestling inflation down to its 2 percent target.

But prices for services, which account for a larger share of consumer purchases, remain a sticky point for the Fed. That was particularly evident in the closing months of 2023, when the gradual slowdown in service price gains hit a wall. Indeed, the so-called supercore inflation index (service prices less housing costs) that the Fed closely watches was still running at a 6 percent annual rate over the final three months of last year. Unless service price gains ease more rapidly, the Fed will have a hard time wrestling inflation down to its 2 percent target.

Just as the healing of supply chain stresses was pivotal in reducing goods inflation, the easing of labor shortages helped relieve wage and price pressures in the service sector. As the health crisis waned, care givers returned to the labor force, the lure of higher wages brought workers off the sidelines and an increase in immigration boosted the labor force. But here too, further progress will be hard to come by. The labor force participation rate rose significantly in 2022 and early 2023, from a low of 61.5 percent to 62.8 percent in August. But the rate has since flat-lined and actually retreated to 62.5 percent in December. The rate never rebounded to the pre-pandemic level of 63.1 percent.

Most Supply Restored

Simply put, the Fed is pondering how much further progress on inflation can come from the supply side. Most of the potential supply of workers on the sidelines have already returned to the labor force, the population continues to age, spurring continuing increases in retirements; and with border control becoming a political flashpoint, immigration should provide less of a boost to labor supply this year. With growth in the labor force poised to slow, several Fed officials believe that only an easing of demand for products and workers will make a further dent in inflation.

That, of course, is where the rubber meets the road. It’s important to recognize that the main beneficiaries of the red-hot job market over the past three years have been lower-wage earners. Thanks to the acute labor shortages in the service sector, where demand boomed after pandemic related lockdowns were lifted, businesses had to offer attractive pay packages to lure workers off the sidelines or from other industries paying higher wages. Since service prices are heavily influenced by labor costs, those wage increases are a major reason service prices have remained elevated, making the Fed’s job of slowing inflation more of a challenge.

That said, the gap between lower and higher wage workers has narrowed considerably, and the reduction in income inequality is a socially desirable goal that policymakers were happy to see unfolding. However, when the economy weakens and the demand for labor slows, lower-wage workers are usually the first victims to feel the pain, as their jobs are more dependent on discretionary spending that is more likely to be cut early in an economic slowdown. Needless to say, the Fed will have to make some difficult decisions in coming months. Cut rates too early, and it risks undoing the progress made on inflation. Wait too long and it risks sending workers, particularly lower-wage earners, flocking to the unemployment lines. Our sense is that the economy retains enough strength to justify holding off rate cuts until May, but it will be an anxious waiting game.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking dl’[email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |