Noisy Data Complicates Fed Policy

With a presidential election looming, geopolitical tensions escalating, and a central bank considering a major shift in its policy stance, 2024 looks to be an eventful year with a wide range of possible outcomes. So far, the financial markets are taking a “what, me worry?” attitude, as stock prices have hit new records and businesses have had little trouble raising huge amounts of funds in the capital markets. One reason for market complacency, of course, is that unfolding developments and the swirl of uncertainty facing the nation have hardly put a dent in the economy. The job market is still chugging along, incomes are rising amid easing inflation, consumers are grumbling about high prices and interest rates but continue to spend, and household as well as business balance sheets are in good shape.

Simply put, recession fears that were so rampant last year have been put on the back burner, as the economy seems able to weather anything thrown at it, including a pandemic, wars, inflation, and skyrocketing interest rates since the spring of 2022. A sense of invincibility, however, is not an effective weapon against adversity. Indeed, history shows that the economy usually appears muscular in the months before a recession strikes, much like the current backdrop. But when things start to go bad, they tend to go bad quickly and are difficult to stop. That’s not to say a burst of misfortune is inevitable. A soft landing where the stars align to bring about sustained growth, high employment, and low inflation may well be in the future for the U.S. economy; indeed, many more commentators believe that such a Goldilocks scenario has a chance of materializing than a few months ago.

But luck, as well as smart decisions, will need to play a role in the process. Luck would involve an easing of Mid-East tensions, limited economic ramifications from the Russia/Ukraine conflict, and a calm political process leading up to the November elections. Smart decisions will also be required of policy makers who are debating when and by how much to cut interest rates this year. But smart decisions mean that the Federal Reserve needs smart data to guide it, and that may be difficult to obtain early in the year. That’s when incoming data are corrupted by unpredictable winter weather, and by the resetting of prices and wages that may temporarily give a distorted picture of underlying inflation and income trends. To be sure, policy makers are not flying blind; but any misinterpretation of reality due to faulty information can lead to misguided policy decisions that have harmful economic effects down the road. Hopefully, spring will bring more clarity on the economy before it is too late.

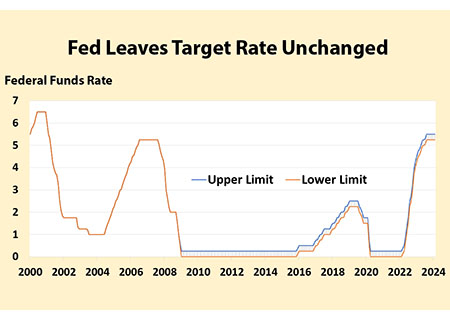

The Fed Stays the Course

In the waning months of 2023, most economists thought the economy was poised to roll over and would need the Fed to step in quickly to stave off a recession. After all, inflation had tumbled dramatically over the second half of the year and the 2 percent target sought by policy makers seemed well within reach. Slowing growth, the ongoing healing of supply chain bottlenecks, and the potential bite from the Fed’s aggressive rate hiking campaign were coalescing into a receptive backdrop for the Fed to start cutting rates sooner rather than later.

But as the calendar turned to 2024, some key data refused to follow the script. Both job creation and inflation came in hotter than expected in January and February, prompting the markets to rethink the wisdom of a growth-stimulating rate cut. To its credit, the Fed had steadfastly resisted calls for an imminent rate cut, clashing with traders who were pricing in not only an early reduction in rates, but at least four more before the end of the year. Following the data for January and February, however, that divide between the Fed and the markets has closed; for the first time in a while both traders and policy makers are on the same page.

Unsurprisingly, at the March 19-20 policy meeting, Fed officials reaffirmed their “wait-and-see” approach, keeping the policy rate unchanged at the 5.25-5.50 percent range in place since last July. Also, unsurprisingly, the markets applauded this stand-pat approach, recognizing that the risk of stoking higher inflation was just as high as the risk of bringing on a recession. In its updated projections Fed officials still expect to cut rates three times this year, but the starting date remains up in the air.

Showing Patience

Showing Patience

As always, the Fed is being data dependent. As Chair Powell reiterated at his post-meeting press conference, inflation is moving in the right direction (down) but not as quickly as hoped. By itself, that won’t derail the predicted rate cuts; inflation does not have to hit the 2 percent target for the Fed to pull the rate-cutting trigger, only that it is moving sustainably towards that goal. Unfortunately, the data over the first two months of the year suggest that progress on the inflation front may have stalled, as both consumer and producer prices (the cost of goods to businesses) ticked higher.

What’s more, job growth, as noted earlier, also came in stronger than expected. That, in turn, creates more paychecks, which should support demand and give businesses the ability to keep raising prices. No doubt, both the strength in the job market and hotter consumer price data have given the Fed less confidence that inflation will continue to retreat, something that Chair Powell noted in his post-meeting press conference on March 20.

But just as the Fed did not respond in knee-jerk fashion to the steep inflation retreat in 2023 by cutting interest rates, it is not about to overreact to two-months of firmer-than-expected price data by turning more hawkish. As Powell noted, it is unclear if the uptick in inflation in January and February is just a bump in the road, or something more durable. Since Fed officials did not change their prediction of three rate cuts this year that they put forward in December, they still believe that the inflation retreat will resume in coming months. The road will be bumpier, but the last mile to 2 percent was always thought to be the hardest.

Questioning the Data

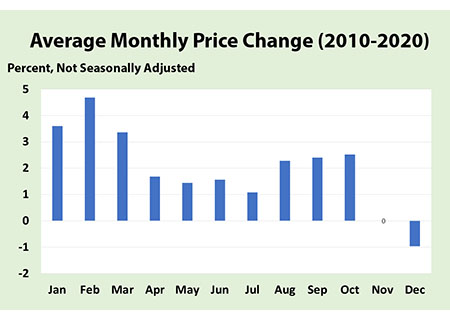

So why is the Fed downplaying the hotter inflation data over the past two months? Historically, the consumer price index in January and February increases faster than in any other month of the year. In the 10 years prior to the pandemic, the core consumer price index, which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is considered more representative of underlying inflation, increased by an average of 4.1 percent at an annual rate, much higher than every subsequent month, and more than double the 1.5 percent average from March through December.

One reason is that businesses reset prices in January to cover wage and other cost increases incurred over the previous year. While this is a recurring phenomenon, the statisticians usually do not fully remove the early-year bump in prices through the seasonal adjustment process. This statistical quirk extends into February because the Labor Department collects data for certain items every other month, depending on the goods and services and their location. The reliability of the winter readings is further diluted by unpredictable weather conditions, which were particularly harsh this January, and may have depressed the response rate in the survey, pushing some outsized price increases into February.

That said, the Fed was undoubtedly irked by the upside inflation surprise, supporting its decision to hold off on rate cuts. Some still believe that holding rates “higher for longer” – which is now the Fed’s playbook – runs the risk of overstaying a restrictive policy, sending the economy into a recession. However, policy makers believe that the ongoing strength in the job market diminishes that risk, particularly since wages are rising at a solid clip, generating the purchasing power to support consumption. As long as consumers continue to spend – which drives about 70 percent of total economic activity – the risk of a downturn is slim.

Strong Hiring Will Not Derail Rate Cuts

That, of course, is where the rubber meets the road. Just as inflation and job growth came in surprisingly hot, consumers turned more frugal than expected to start the year, as retail sales slumped in both January and February. To be sure, the early-year hiatus may be nothing more than consumers taking a breather, following their shopping spree over the holidays in the final months of 2023. What’s more, although they are shunning goods sold at retailers, households are still spending on services — traveling, going to concerts (hello Taylor Swift), sporting events, and generally partaking of experiences that were delayed during the pandemic.

Consumers may not be ready to zip up their wallets and purses as real incomes are growing at a decent pace, thanks to solid job growth, and households in the aggregate are in good financial shape. Nor does the strength in the job market cause much of a concern to policy makers, despite the potential wage-price spiral that an overly tight labor market threatens to bring about. As Fed Chair Powell noted at the latest post-meeting press conference, the steepest decline in inflation last year occurred alongside accelerated job growth. Simply put, the strength of the economy last year was driven as much by expanded supply as demand. Goods became more available, immigration boosted labor supply, and people returned to the labor force.

The Fed is counting on more supply-driven growth that will continue to ease wage and price pressures this year, paving the way for rate cuts. That’s why the upgraded forecast presented at the March 20 policy meeting included a higher growth outlook with only a modest uptick in inflation expectations. That said, the Fed is understandably coy about when it expects to start the easing process, setting the stage for months of speculation in the financial markets that will no doubt spur more volatility than otherwise.

The firm readings on prices early in the year may have overstated actual inflation, and the trend is likely heading lower. Beside the seasonal quirks mentioned earlier, there is a lot of disinflation in the pipeline, particularly for goods, and the elevated pace of housing costs – which had a big influence on the January/February inflation data – does not capture the significant slowing of market rents currently unfolding. They will, however, soon enter the official data and drag down the inflation rate later in the year. It’s widely expected that the first rate cut will likely come in June or July, a time-table that seems appropriate. By then, the Fed will have three more reports on inflation and jobs, which should give a more accurate picture of where the economy stands – and what policy changes will be needed. The wintry mix of noisy data will soon give way to more clarity as normal weather and price-setting conditions return.

Brookline Bank Executive Management

| Darryl J. Fess President & CEO [email protected] 617-927-7971 |

Robert E. Brown EVP & Division Executive Commercial Real Estate Banking [email protected] 617-927-7977 |

David B. L’Heureux EVP & Division Executive Commercial Banking [email protected] 617-425-4646 |

Leslie Joannides-Burgos EVP & Division Executive Retail and Business Banking [email protected] 617-927-7913 |